Keeping Indian Children Connected with Family and Culture

- Kathryn Fort, J.D.

- Director, Indian Law Clinic

- Associate Director, Indigenous Law and Policy Center

- College of Law

Project Overview

- The Indian Child Welfare Act Appellate Project provides pro bono services to tribes on ICWA cases and gives Indian Law Clinic students the opportunity to gain experience working with tribal representatives, conducting legal research, drafting appellate briefs, and developing policy papers.

Products/Outcomes

- Services provided by Fort and students in the Indian Law Clinic facilitate faster and more successful appeals in Indian child foster placement cases.

- Students in the ICWA Appellate Project gain valuable skills and experiences unique to those in other programs.

- The ICWA Appellate Project and the MSU Indigenous Law and Policy Center strengthen a pipeline of Native students into MSU's Law School and into legal careers, especially those involving much-needed tribal legal representation.

Partners

- Anita Fineday, Managing Director of Indian Child Welfare Programs, Casey Family Programs

- Jack Trope, Senior Director of Indian Child Welfare Programs, Casey Family Programs

- Shayne Machen, Former Tribal ICWA Attorney, Little River Band of Ottawa Indians

- Many tribal partners

Form(s) of Engagement

- Community-Engaged Service and Practice

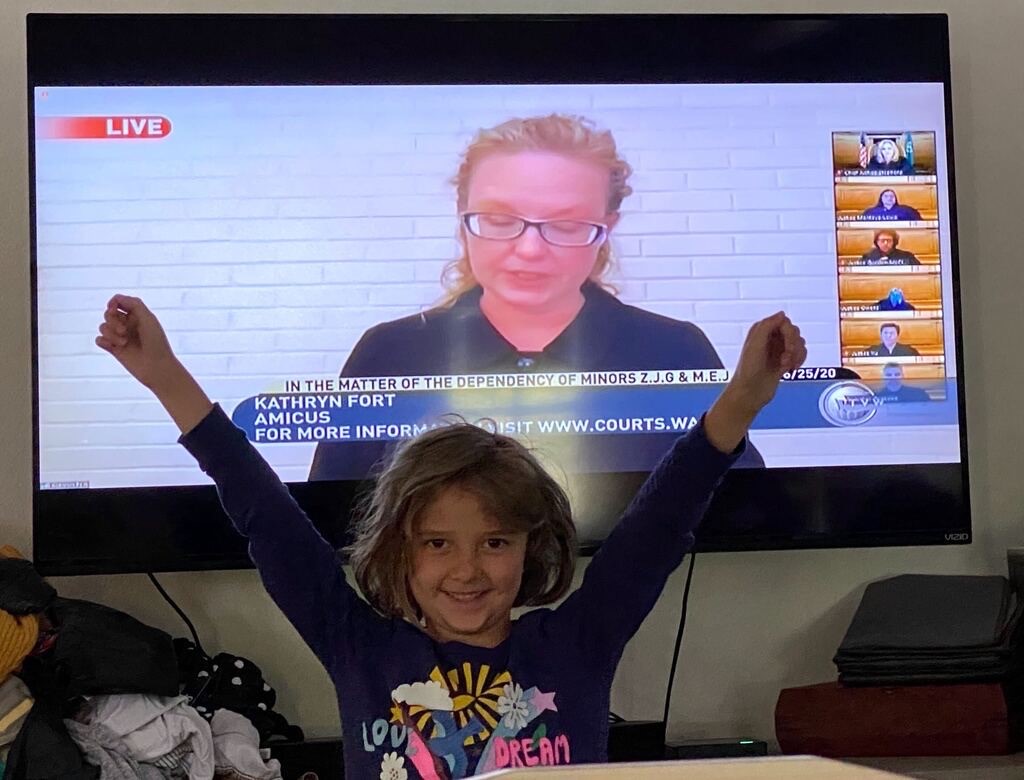

A young Squaxin Island Tribe descendant cheering on Kate Fort during oral arguments in the Washington Supreme Court.

Prior to the enactment of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978, American Indian/Alaska Native children were routinely taken away from their extended families, tribes, and cultures, often across state lines. Based on testimony about the long-term impacts following decades of detrimental policies and practices, Congress enacted ICWA in 1978 as a federal law establishing standards for the foster and adoptive placement of American Indian children and enabling tribes to be informed and involved in these placements.

Kathryn (Kate) Fort, director of the Indian Law Clinic in MSU's College of Law, has been representing tribes across the country on ICWA cases for her entire career, becoming a national expert on this area of law. In 2015, with funding from the Casey Family Programs, she started the Indian Child Welfare Act Appellate Project, an initiative of the Indian Law Clinic that supports tribes in legal cases involving the placement of Native children.

"The belief has been that the Indian Child Welfare Act helps to reduce the amount of time children have to spend in foster care, increases reunification with parents, or ensures a kinship placement in their community," said Fort. "All of those things align really well with the broader Casey Family goal."

Partnering with the Casey Family Programs

Casey Family Programs is the nation's largest operating foundation focused on safely reducing the need for foster care placements. Through their Indian Child Welfare Programs Office, located in Denver, Colorado, they work on national and tribal initiatives through partnerships that honor tribal sovereignty and build tribal capacity in the area of child welfare. Casey Family Programs has been supporting Kate Fort and the Indian Law Clinic for a decade.

In 2011, managing director of the Indian Child Welfare Programs at Casey Family Programs, Anita Fineday, contacted Fort and asked if she would be willing to participate in a program that sought to measure compliance with ICWA through court observation. So, with an initial $25,000 stipend from Casey Family, Fort set up a project with her law students where they went to court rooms in Ingham and Wayne Counties and observed child welfare hearings to determine compliance.

Meanwhile, through her own research and experience filing briefs on appeal cases, Fort noticed that tribes who were succeeding with their appeals typically had access to a dedicated appellate attorney. Unfortunately, most tribes don't have that access.

"The thing is, most tribes don't have the capacity to have a child welfare attorney, much less an appellate child welfare attorney," explained Fort. "So I proposed to Casey Family that we really needed essentially a legal center for the Indian Child Welfare Act, where we could use the Indian Law Clinic to develop best practices in ICWA appellate cases and to use students to draft either amicus or principal briefs in ICWA cases."

So The ICWA Appellate Project was started in 2015 as a clinical initiative providing pro bono legal services to tribes in Indian child welfare proceedings.

Students Receive Training While Assisting Tribes

With close faculty supervision, students conduct legal research, draft appellate briefs, and develop policy papers for tribal governments and organizations. The work that the students produce is not only a benefit to tribes; it is a unique and valuable experience for students. "This kind of training—learning how to do that kind of research and writing—is very different from anything they've ever encountered in law school prior to joining the Clinic," said Fort. And since 2015, Fort and her students have taken on increasingly complex ICWA cases, often involving state Supreme Court and federal court litigation involving ICWA.

Fort works closely with Jack Trope, J.D., a senior director in the Indian Child Welfare Programs at Casey Family Programs. Trope works on national and local initiatives, including promoting compliance with ICWA and access to the Title IV-E Foster Care and Adoption Assistance Program. He is a co-author of the American Bar Association Indian Child Welfare Act Handbook.

"We get involved in tribal/state collaborations in a variety of contexts, often with a goal to promote better compliance with ICWA," said Trope. "Among other things, Casey has filed amicus briefs in some of the most important ICWA cases, in particular those that are heading toward the Supreme Court."

He sees value in pooling the expertise of the Casey Family Programs with the research and resources of MSU's Law Clinic students.

"We saw that they can really complement all that we were doing—that they're a good resource for all things ICWA," said Trope. "There's a tremendous level of expertise, and that expertise is kept up-to-date. A lot of the people who are working in the field are not necessarily honed-in that way and may or may not be up on everything that's going on, as much as the Clinic is. So the Clinic is a good resource to tap into for people who are involved in these cases and need up-to-the-minute information about an issue or about what might be going on in another state that they don't know about, that might be relevant to their case. The Clinic is filling a need out there that nobody else does quite as systematically."

Overcoming Barriers

Former students of Kathryn Fort (center, holding one of their children). All are tribal citizens, all attorneys, all MSU Law graduates, and all working for and with tribes. From left to right: Elise McGowan, President Whitney Gravelle, Mike Hollowell, Leah Jurss.

While ICWA has helped ensure that Native children are placed in family and tribal homes, Native children are still 2.5 times more likely than other children to be placed in "stranger" homes. This is often due to the barriers tribes face when appealing ICWA cases, such as lack of access to an in-house attorney dedicated to child welfare, lack of access to extremely cost-prohibitive databases, and geography—the physical location of Native children.

"A vast majority of Native American people do not live on their reservations, and the Indian Child Welfare Act applies no matter where they live in the country," explained Fort. "So a huge barrier, and one that I deal with the most, is tribes that have cases in states that they're not located in. So I spend a lot of time trying to find local attorneys and people who are willing to file documents on behalf of tribes in different states."

According to Fort, the Law Clinic's programs can help lower these barriers.

"That's the beauty of our clinic," said Fort. "Those are all barriers that we're able to help tribes overcome. We provide our services pro bono. I'm a trained appellate attorney and I work nationwide, so I'm usually able to find a local attorney to file documents and briefs. And we have access to those large legal research databases."

Working with Tribes for Successful Case Resolution

This is tough, often time-consuming work. Because the welfare of a child and family is always at stake in ICWA cases, a faster resolution to a case is ideal. So Fort considers a case successful when the tribe or tribal representative finds a solution without going through a long appeal process.

"I spend a lot of time talking with tribes who are thinking about appealing or are dealing with an appeal to try to figure out how to shorten that; how to come up with a compromise; how to figure out a way to address the issue before they have to go on appeal," said Fort.

Shayne Machen is a former tribal ICWA attorney who provided oversight and representation to tribes on child welfare cases in several capacities, including tribal prosecutor and whistleblower investigator. Working with Fort and her students at the Clinic helped facilitate successful outcomes for her and other tribal child welfare workers.

"The assistance of Director Kate Fort and the MSU Indian Law Clinic was invaluable," said Machen. "It would have been a significant strain on tribal resources to hire a national ICWA expert like Director Fort to consult on cases. Thanks to the MSU Indian Law Clinic, Director Fort was never more than a phone call away. She and her staff were deeply committed to assisting tribal governments and were clearly passionate about Indigenous families and communities. It is not an overstatement to say that we could not have done our work well without her. Tribal governments cannot compete with the resources state governments, the judicial system, and county prosecutors have access to; having MSU Indian Law Clinic available to answer questions, conduct research, and connect tribes to resources gave tribal governments an advantage they would not otherwise have."

Indian Law Clinic Alumni Carry on the Good Work

While the work is tough, Fort has the satisfaction of knowing that her students, many of whom are, themselves, Native American, are graduating from MSU prepared to carry the work forward.

"It's fantastic! I work with my former students all the time," said Fort. "A lot of them are in-house attorneys. One of them is a tribal leader—she's the tribal president of her tribe. Lots of them work in-house for their tribe here in Michigan and around the country. I run into my former students all the time! It's the best part of the work."

Kate Fort is a popular guest lecturer and has written numerous articles on ICWA. She is the author of American Indian Children and the Law (Carolina Academic Press), teaches Federal Indian Law classes, and contributes to the Indian law blog, Turtle Talk.

- Written by Amy Byle, University Outreach and Engagement

- Photographs courtesy of Jennifer Whitener and Elise McGowan Cuellar