Think Piece: On Land Grant Universities and Being My Brother's Keeper

- Marvin H. McKinney

- Senior Consultant and University Senior Fellow

- University Outreach and Engagement

In 2006 I was involved with a collaborative partnership, Promoting Academic Success (PAS), which Michigan State University entered into with a local school district that had expressed concern regarding the academic achievement of its young boys of color. This project, which lasted six years, developed a multigenerational mentoring component, utilizing college student males of color who trained high school student males of color to tutor and mentor young males of color in pre-kindergarten through third grade. The goal was to augment and supplement classroom learnings and the academic development of all participants, from the preschoolers to the college students.

In 2006 I was involved with a collaborative partnership, Promoting Academic Success (PAS), which Michigan State University entered into with a local school district that had expressed concern regarding the academic achievement of its young boys of color. This project, which lasted six years, developed a multigenerational mentoring component, utilizing college student males of color who trained high school student males of color to tutor and mentor young males of color in pre-kindergarten through third grade. The goal was to augment and supplement classroom learnings and the academic development of all participants, from the preschoolers to the college students.

The program drew upon the expertise of College of Education faculty to design and deliver a teacher training component and a children's summer learning camp. Community partners became involved to lend funding support and community connections. The local project implementation team consisted of 28 school district teachers, administrators, early childhood program and community agency administrators, and university faculty, staff, and students. Evaluations of the project, both formal and informal, documented positive results for all parties, and the participating young males of color demonstrated a positive learning trajectory over the six-year life of the program based on standardized measures.[1] The PAS model has been implemented in two summer programs with middle school children (in 2013 and 2014), and further evaluation of this adaptation is planned. The resource manual for program implementation is available online.[2]

Another stellar example of a universitycommunity collaboration to address educational obstacles faced by young boys and men of color is My Brother's Keeper (MBK), a mentoring program that operates out of the Paul Robeson Malcolm X Academy in Detroit. Assistant Professor Austin Jackson of MSU's Residential College in the Arts and Humanities leads the program, with guidance and support from partners MSU Professor Emerita Geneva Smitherman, who was the founding director of MBK, and Jeffrey Robinson, who was the first graduate of MSU's African American Studies doctoral program in 2008 and is now principal of the Academy. The story of My Brother's Keeper is reported elsewhere in this issue of the Engaged Scholar Magazine (pp. 14-19), so I will not repeat it here, but this effort also represents a longstanding partnership with deep academic and professional connections.

The name of Dr. Jackson's program, My Brother's Keeper, is a phrase that lately has been resonating widely with the faith and philanthropic communities. President Obama picked up on it with his recent announcement of a new national initiative—also titled My Brother's Keeper[3] —directed at the segment of society that is represented by my brothers and their sons.

Having spent a lifetime personally and professionally involved with the plight of under-represented men of color in general and with African American men in particular, I had a cautiously optimistic reaction to the rollout of the national My Brother's Keeper initiative in February 2014. The "bully pulpit" of the presidency, a gathering of committed leaders, and a boatload of scholarly research all gave cause for both the caution and the optimism. This oxymoronic reaction happens when you really want to believe, but your life experiences encourage you to take a wait-and-see posture as a hedge against psychic and emotional deflation.

How We Got Here (an Abbreviated Political Chronology) and Where We Are Going

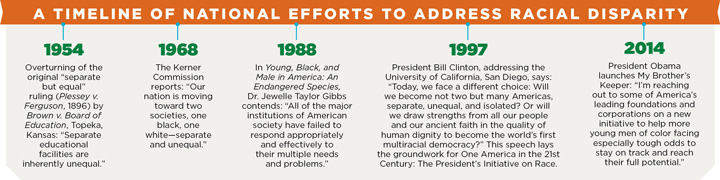

In a January 28, 2014, press release, the President stated, "I'm reaching out to some of America's leading foundations and corporations on a new initiative to help more young men of color facing especially tough odds to stay on track and reach their full potential." A month later he called together civic, faith, philanthropic, and corporate leaders to announce the launching of My Brother's Keeper, which he described as a new effort to positively alter the life trajectory of boys and young men of color. It was more than mere coincidence that three of Michigan's major foundation leaders—Kellogg, Kresge, and Skillman—were in attendance and pledged their commitment and financial support.

In his comments, President Obama cited the discouraging fourth grade reading and math scores for Black and Latino boys. He also cited the litany of rotten statistics that we all know too well—high school dropout rates, incarceration rates, unemployment rates, and homicide rates—many of which have their genesis in limited resources and opportunities. He emphasized the point that despite sometimes overwhelming odds, many young men and boys in such circumstances do thrive, but not enough.

This was not the first national call for attention to the lack of opportunities for vulnerable, limited-resourced men of color. The issues surrounding these men, who have been marginalized by social, educational, and economic disenfranchisements, are not a new phenomenon.

In 1968, as a young teacher of 10-year-olds, I read with interest the report by the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, historically known as the Kerner Commission Report. Speaking to all indicators of well-being, it stated that "our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal."

Twenty years later, Dr. Jewelle Taylor Gibbs, referring to the title of her nationally acclaimed book, Young, Black, and Male in America: An Endangered Species,[4] stated, "All of the major institutions of American society have failed to respond appropriately and effectively to their multiple needs and problems."

In 1997 President Bill Clinton acknowledged the nation's changing demographics and sought to create a broader conversation, more inclusive of vulnerable populations. In a commencement speech to the University of California, San Diego, after citing the 1968 Kerner Commission Report, he said, "Today, we face a different choice: Will we become not two but many Americas, separate, unequal, and isolated? Or will we draw strengths from all our people and our ancient faith in the quality of human dignity to become the world's first multiracial democracy?" Clinton's address laid the groundwork for the creation of a national advisory board, One America in the 21st Century: The President's Initiative on Race, which listed four broad goals. Goal Four was to "identify, develop, and implement solutions to problems in areas in which race has had a substantial impact, such as education, economic opportunity, housing, health care, and the administration of justice."

Thus, for the better part of the 20th Century, even while recognizing that we have more people of color enrolled in colleges and universities than ever before and more people of color classified as middle class, we continually allowed large segments to be excluded from participating in the American Dream.

"...with a service-oriented student body, land grant universities are poised to make a positive difference in the academic success of young boys."

President Obama's My Brother's Keeper program seeks to be the catalyst for altering the life trajectory of this group by enlisting the private sector to get in front of the issue with funding, organization, and expertise.

Is this a formula for success? Or will it be another example of national exposure but failed opportunity, where we continue to see 50% graduation rates in some of our urban areas, continued double digit unemployment rates, and one out of four men of color between 18 and 30 tethered to the criminal justice system? These are very complex issues that cross political ideologies as well as demographic identities. Many efforts have been put forth over the years, perhaps most noticeably the overturning of the original "separate but equal" ruling (Plessey v. Ferguson, 1896) by the Brown v. Board of Education, Topeka, Kansas, decision (1954) that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." As a nation, we have been at the precipice of equal opportunity for a very long time. The optimism at this time comes from the reality that the President has again called it out.

My Brother's Keeper and Land Grant Universities

My Brothers' Keeper is a bold and courageous move, but are there enough different voices at the table? Perhaps the voices should include representatives from colleges and universities in general and land grant colleges and universities in particular. For many U.S. citizens, these institutions have long served as the portal to becoming economically viable and self-sufficient. The present-day economy requires workers to be tech-savvy and information-directed. Moreover, higher education provides an opportunity to connect to similar as well as dissimilar people, broaden one's world view, and grow and develop in a safe and controlled environment.

Unfortunately, one significant segment of the population lags behind all others in terms of workforce participation and post-secondary institution attendance. The application, acceptance, enrollment, matriculation, and graduation rates of racial and gender groups indicate that certain males of color continue to struggle to thrive in higher education. To address this issue, land grant institutions can play an instructive and pivotal role through outreach and extension services. Over the years land grant institutions have accumulated a wealth of knowledge about how to democratize education and they have a responsibility to educate the citizens of their respective states.

Without question, some extension and community service functions would need to be refocused in order to address the ambitious agenda of My Brother's Keeper. But with public funding and a public mandate, with work already underway in limited-resource communities, and with a service-oriented student body, land grant universities are poised to make a positive difference in the academic success of young boys. The country's land grant institutions possess time-tested traditions of public service to the people who need it. Many of us remain optimistic about the possibilities, and we envision a time in our collective future where academic success for all children from challenged communities is the norm and not the exception. With the full support of our public land grant universities, My Brother's Keeper may be an opportunity to contribute to more equitable academic opportunity.

Sources

- McKinney, M., Hernandez, R., Lee, K. S., Farrell, P., Sáenz, G., & Tichenor, C. (In preparation). Engaging schools and communities to close the achievement gap: The PAS program.Return to text

- F2 Farrell, P., Sáenz, G., Davis, J. L., Keck, S., & McKinney, M. (2012, August). Promoting Academic Success resource manual. East Lansing: Michigan State University. Retrieved from: http://ucp.msu.edu/documents/PASmanual_091412_lores.pdfReturn to text

- No relation, other than philosophical, to Dr. Jackson's program at the Paul Robeson/Malcolm X Academy in Detroit.Return to text

- Gibbs, J. T. (Ed.). (1988). Young, black, and male in America: An endangered species. Westport, CT: Auburn House.Return to text

- Written by Marvin H. McKinney, with assistance from Allen Buansi, Juris Doctor candidate, University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill