Ethics and Development During the Year of Global Africa

- Stephen L. Esquith

- Dean

- Residential College in the Arts and Humanities

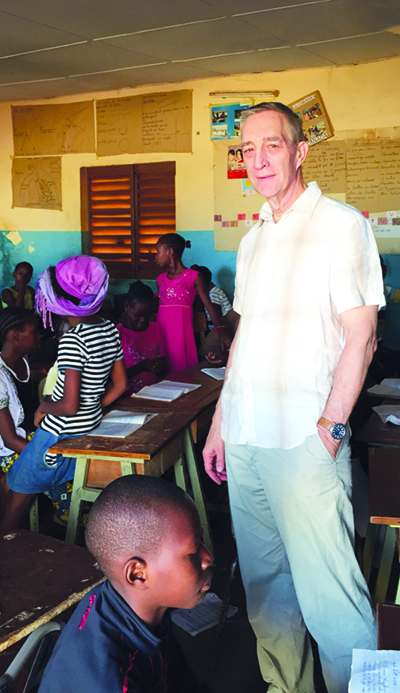

The Mali Picture Book Project, Ciwara School, Kati, Mali, October 2016.

The Year of Global Africa is a time to celebrate the strong and productive relationships that Michigan State University has with its many partners across the continent of Africa and throughout the African diaspora. One dimension of this history is the conscious attention that has been paid by all the participants to the ethics of development. As our relationships have grown over the past 60 years, so too has our understanding of what it means to be engaged in mutually beneficial development projects. The most recent chapter, the Alliance for African Partnership, highlights the ethical dimension of development with our African partners in exemplary ways.

The Year of Global Africa is a time to celebrate the strong and productive relationships that Michigan State University has with its many partners across the continent of Africa and throughout the African diaspora. One dimension of this history is the conscious attention that has been paid by all the participants to the ethics of development. As our relationships have grown over the past 60 years, so too has our understanding of what it means to be engaged in mutually beneficial development projects. The most recent chapter, the Alliance for African Partnership, highlights the ethical dimension of development with our African partners in exemplary ways.

When we think of ethics, we often think of doing the right thing. It is a practical orientation toward others, not merely a moment of honest self-reflection. How should we care for the needy? How should we meet our moral responsibilities to others? How should we respect one another as fellow citizens?

These positive duties are matched by questions about the obstacles we face and the dangers surrounding ethical conduct. The don'ts, if you will, not just the do's. For example, don't treat others as mere objects but as autonomous agents in their own right; don't break your promises. What makes ethics, including the ethics of development, challenging and more than a list of do's and don'ts, are the dilemmas that inevitably arise. Do's will conflict with other do's; for example, caring for the needy may require that we limit the things we can do for family members or fellow citizens. And when you choose between these positive duties, you also may find yourself having to break a promise or violate some other don't as well. This is especially true in development projects where hard ethical choices are unavoidable. To paraphrase the philosopher Isaiah Berlin, we are doomed to choose and every choice will have its costs and benefits. In this essay, I will call these hard choices problems, and they come in two forms.

Problems in and of Ethics and Development

It is initially useful to think of ethics and development in terms of two types of problems: ethical problems in development and the more general ethical problem of development.

Ethical problems in development are problems that moral philosophers might be able to help others solve. For example, should transgenic crops be introduced to reduce costs and increase production in poor countries, that is, would the risks and costs outweigh the benefits? Moral philosophers can help sort out and compare these risks, costs, and benefits. Or, should primary school education in poor countries be conducted in native languages rather than the official country language? Moral philosophers shouldn't try to answer these questions for others, but they can help them separate apples and oranges.

The ethics of development, on the other hand, focuses on the question of what development means and whether it is a good idea. Are international and multilateral organizations dominating development strategies at the expense of poor countries? If poor countries are going to avoid the poverty traps that have persisted despite or perhaps because of this kind of foreign assistance, are there alternative conceptions of development that are less harmful to poor countries? This distinction between ethical problems in development and the ethics of development, while initially useful, may not be as clear as it first appears. One thing that makes some conceptions of development ethically suspect is that they may make it difficult to solve ethical problems in development. If development is carried out by outsiders or in a top-down way, that may make it hard to solve ethical problems in development. The value of greater self-reliance or mutual reliance in development is that it may be more likely to solve ethical problems in development.

Key Themes

The Year of Global Africa is organized around three key themes, and embedded in each theme are ethical questions in and of development.

Global Africa. Africa today is a bustling hub of economic growth. It is attracting labor and capital from around the world in new forms of partnership. It is exporting new products and materials along new trade routes. As its population grows, so does its potential for greater prosperity. And with new prosperity and growth come questions of distributive justice. Many African countries enjoy significant natural resources, but this has not always translated into greater well-being for the majority of these countries. But today, for example, Ghana is developing its oil reserves and expanding cocoa production in a manner that hopes to avoid the problems that have attended earlier resource-rich countries. Increasing total production is not enough. It must be accompanied by better paying jobs for more Ghanaians. How should total production be balanced against increased employment and higher wages? This is a major ethical problem in development.

Unity through diversity. Local knowledge, abundant natural resources, and vibrant cultures constitute a diversity that distinguishes peoples from different African states at the same time that they come together in many hybrid forms, from fabric art to agricultural products to music and film. This hybridity poses several ethical challenges. For artists, one question is the impact of commercialization on the quality of their work and their cultural identity. How much can they change their art work to attract tourists or sell to a larger export market without losing what makes the work meaningful within their own culture? Are these new hybrid forms of visual and performing art meaningful and valuable in an evolving, more inclusive culture?

Hybridity is often used to describe a stronger, more resilient species. While greater adaptability to a changing environment is valuable, are there moral limits to hybridization? If so, what are they when it comes not only to music and visual arts, but also to food crops? In other words, how does one balance this movement toward a new form of hybridity against traditional forms of diversity? Should all native languages be preserved, or should all cultures be encouraged, that is, rewarded for adopting a single national language? And how should these decisions be made? This is an ethical problem in and of development.

Partnership. A central theme throughout the Year of Global Africa is MSU's new Alliance for African Partnership, which stresses the importance of reciprocity that honors different ways of knowing in the search for collaborative ways of acting. This theme is particularly important as we struggle to overcome neo-imperial conceptions of development. There are many kinds of partnerships—economic, political, social, and military. My own work has focused on partnerships in peace building in Mali, and I'll use this experience to discuss one particular kind of challenge facing reciprocal partnerships in this context: complicity.

Institutional Complicity in Mali

Stephen L. Esquith with Missoudjie Dembele (left) and Boubacanar Garango (right), the teachers who led the Mali Peace Game in 2015 at the Ciwara School.

Complicity can refer to being an accessory to or an accomplice in an illegal act. It can mean aiding and abetting the enemy in wartime. Complicity also can refer to the failure of bystanders to intervene in harmful acts when they can and should intervene.[1] In all of these cases, whether active or passive, complicity refers to collaborating with a wrongdoer or an aggressor at the expense of an ally. It signals the absence of empathy for and solidarity with those who ought to be allies in a moral and sometimes legal sense. Complicity in this conventional sense is clearly antithetical to reciprocal partnership and therefore to an ethical peace building strategy.

There is another form of complicity that allies engaged in peace building must be wary of and resist. It involves abandoning responsibilities to allies in favor of accountability to an institution.[2] The figures of the institutionally complicit "company man" and the "good soldier" come to mind. In an educational setting, institutional complicity can take the form of protecting the financial solvency or reputation of the school at the expense of the well-being of students or other teachers.

Now, take our AAP global alliance between partners in Mali and the U.S. with its potential for institutional complicity.

After a promising but certainly not trouble-free democratic revolution in the early 1990s, since the military coup and occupation there in 2012-2013 Mali has been an increasingly impoverished and violent society. Today, control of almost half of the country (whose total geographic size equals California and Texas combined) has been ceded informally to separatists, violent extremists, and traffickers of all stripes. The government has declared a state of emergency and in the remaining half of the country it maintains a fragile visible presence, but depends largely on foreign and international military and economic assistance to maintain order.

This is true of the public provision of education throughout Mali as well. In northern territories and much of central Mali, K-12 teachers have abandoned their positions in fear for their lives. At the university campuses in and near the capital Bamako, overcrowding and under-qualified faculty drive the best students who can afford to seek higher education abroad. The dire conditions immediately following the coup of 2012 have only gotten worse.[3]

As the youth population continues to grow, the public education system—where it is still functioning—neither trains students for employment nor prepares them to participate in building peace and democracy.[4] Young girls now more than ever have few alternatives to early marriage. Young boys either can join the military where they are poorly trained and poorly led, or they can succumb to the siren songs of separatists and religious extremists. Mali is squandering its human resources at a time when it needs to be investing in them for its very survival as a democratic political society.

The title of our AAP project is Countering Violent Extremism in Mali, but the subtitle is actually more revealing: Critical Reasoning, Moral Character, and Democratic Resilience Through Peace Education. The participants in our project (the Malian Institut pour l'Education Populaire (IEP), the MSU Residential College in the Arts and Humanities (RCAH), and the Malian Université des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines de Bamako (ULSHB)) are political allies and economic partners in a multi-faceted local initiative designed to serve as a beacon and a catalyst for democratic political education.

However, our collaboration is not without its ethical dangers. Each of the partners faces its own particular version of institutional complicity. Operating within a constellation of complex institutions driven by their own survival imperatives, they run the risk of making unethical compromises to preserve the institution at the expense of their primary objectives.

IEP and the Ciwara School have had to concentrate on the lower grades at the expense of older students, RCAH has had to concentrate on investments in recruitment activities, and ULSHB has had to charge its own private tuition despite being a public university. We have all done this to keep our institutions afloat at the expense of reducing the programs that we are there to provide.

These hard choices reflect the ethical dilemmas in development and also the contested meaning of development in education. Balancing on this razor's edge takes a partnership built upon trust and cooperation. The Year of Global Africa provides us with an opportunity to learn from one another as we address these problems in and of development.

Source

- Guiora, A. N. (2017). The crime of complicity: The bystander in the Holocaust. Chicago: Ankerwycke. Back to Article

- Docherty, T. (2016). Complicity: Criticism between collaboration and commitment. London: Rowman & Littlefield International. Back to Article

- Dougnon, I. (2013, March 10). In a time of crisis, why are academics so quiet? University World News, Issue 262 [online]. Retrieved from: http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20130308124745395 Back to Article

- Bleck, J. (2015). Education and empowered citizenship in Mali. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Back to Article

- Written by Stephen L. Esquith, Residential College in the Arts and Humanities

- Photographs courtesy of Stephen L. Esquith