A People's Historian

- Nwando Achebe

- Jack and Margaret Sweet Endowed Professor of History

- Department of History

- College of Social Science

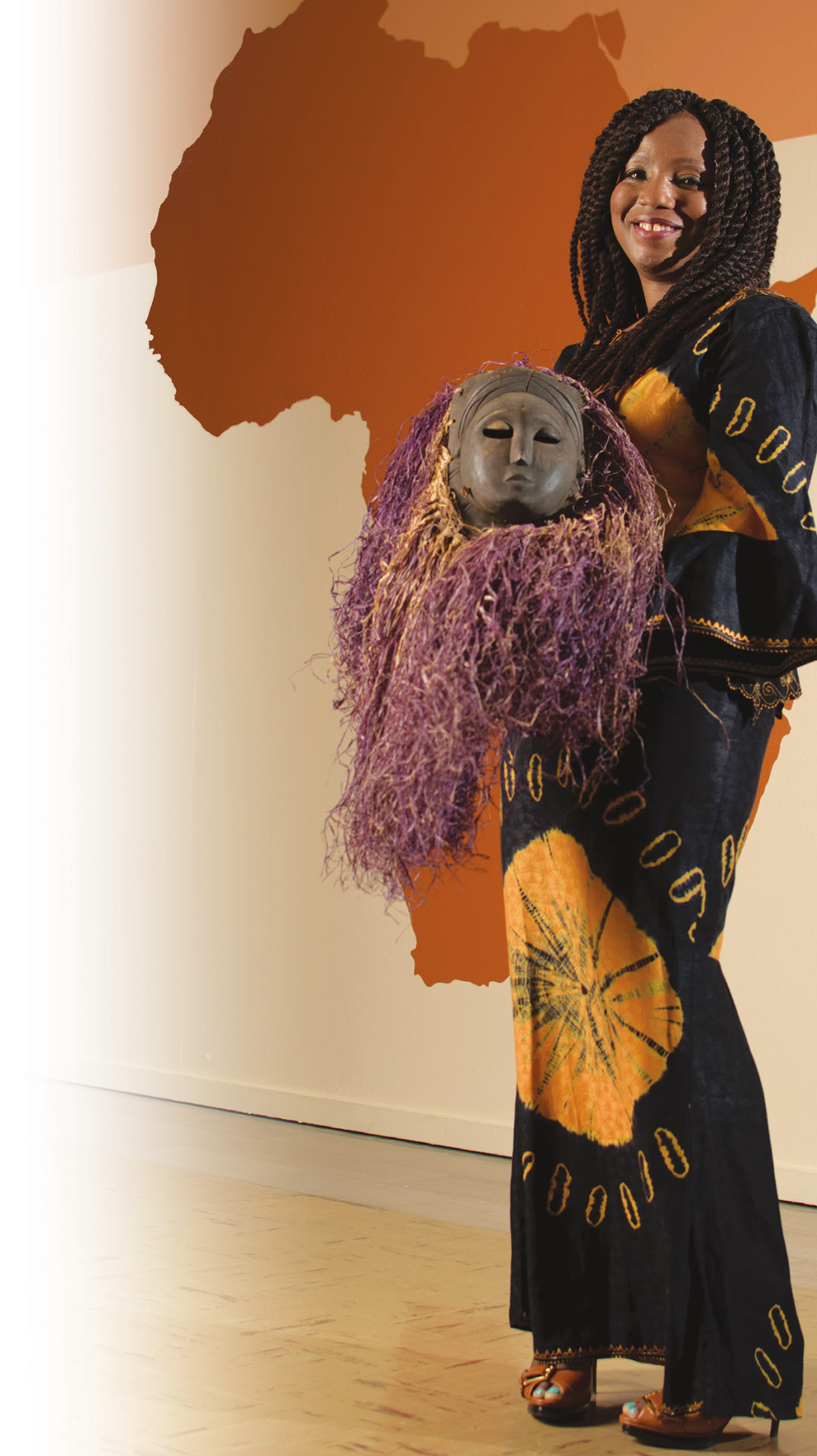

Nwando Achebe holds a mask used in religious practices in Nigeria. The spirit of a deceased loved one visits via the mask during a ceremonial performance.

By her own admission, Nwando Achebe's research interests came out of a desire to see herself in history. Born in Nigeria, Achebe's first word was in the Igbo language, and her second word was in English.

By her own admission, Nwando Achebe's research interests came out of a desire to see herself in history. Born in Nigeria, Achebe's first word was in the Igbo language, and her second word was in English.

"I very much identify, first and foremost, as an Igbo woman," she says.

Achebe is an award-winning historian who focuses on oral history in the study of women, gender, and sexuality in Nigeria. She has emerged as a strong voice for West African history.

Her passion to document authentic voices was ignited during her graduate study years in African history at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). She was infuriated by the images of African women that she and fellow students were assigned to read.

"My professors gave us texts to read about African women, and I could not see myself in those histories," said Achebe. "One professor had us read this article, entitled "Beasts of Burden: The Subordination of Southern Tswana Women."[1] There were about four African women in the class and we were all pissed off! Our quarrel was not just with the title of the piece. What worried me, even more than the objectionable title, was the divergence of opinion on how to interpret the evidence the writer used in her determination that the women she was studying were in fact beasts of burden."

Family Influence

When Nwando Achebe was young, she thought everyone's father was famous. Her father, Chinua Achebe, wrote Things Fall Apart (1958), a work of fiction that achieved worldwide attention. It is frequently referenced as one of the most important works in African literature, and Chinua is considered one of the founding Nigerian literary leaders who incorporated traditional oral culture into his storytelling. Now studied in classrooms across the United States and Europe, the novel provides a starting point for conversations about race, religion, politics, social justice, and social power constructs.

The first two years of Nwando Achebe's life were spent in Nigeria; the next four were in the U.S., then back to Nigeria from ages 6-17.

Storytelling was a consistent activity in the Achebe household. The family often spent evenings in a circle, with the elder Achebe telling them folk tales and singing songs. Her parents conveyed a love for their country and their culture that Nwando Achebe absorbed during her growing up years.

"I am a child of the crossroads. A child born and raised in Nigeria, but also, one who has lived most of her life in the U.S., and studied in American universities. I identify, first and foremost, as an Igbo woman because my parents instilled in my siblings and I a love for our culture and our language; and it didn't matter where we happened to be living at the time," said Achebe.

"I don't believe in generalizations, but the average American does not have a positive view about Africa; and this is because of the images that we are constantly being fed about Africa. Turn on the television, and all you see is warfare and pirates—then, late night infomercials encourage us to give African youngsters a dollar, to help save their lives. Africa thus becomes this place where nothing good happens, a place that demands our help. Good intentions, while good, do not always solve problems. Sometimes they create new problems. What Africa needs is conversation. For both sides to have a seat at the table, and talk. Truly listen to one another. Once we've had these conversations, then both worlds can engage one another on an equal and respectful footing," said Achebe.

"With regards to my African history teaching, I begin each one of my classes with what I call my "Stop Word" list. These are words that I believe "stop" conversation between Africa and the rest of the world. They tend to be words that are disparaging and condescending. However, sometimes the words are not as outrageous as one might think. My students and I read these words out loud, and have a conversation about why the words are problematic when used to depict or explain Africa. I want students to have an opportunity to speak one on one with an African woman who is able to present Africa to them in a way that does not distance Africa; does not present Africa as this dark continent where crazy things happen," said Achebe.

Path to MSU

During her field work, Achebe has received many gifts, including Igbo pottery similar to this clay pot. Pottery is one of the oldest of Igbo cultural traditions, primarily performed and maintained by women.

Nwando Achebe sees her place at Michigan State University as a natural iteration of her life journey. "It made sense for me to be at MSU," she said.

After completing a bachelor's degree in theater arts from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Achebe headed to UCLA intending to become a documentary filmmaker. She earned a master's in African area studies, and then her Ph.D. in history, studying West Africa and women's/gender studies.

Achebe's first book, Farmers, Traders, Warriors, and Kings: Female Power and Authority in Northern Igboland, 1900-1960, was based on her dissertation at UCLA. The work centers around a 60-year period in Igboland and the gender dynamics in the Nsukka Division. Achebe's historical narrative points to female kings and warriors that held positions of power, and challenges conventional global beliefs that men alone are societal leaders.

"When I was working to convert my dissertation into my first book, my father advised that I 'never lose sight of the story that I am trying to tell.' And that advice has stayed with me, always. As historians, our job is to tell stories. We tell stories that actually happened," said Achebe.

She was recruited by MSU while serving as an assistant professor at the College of William and Mary in Virginia. "I grew up in Nsukka. I work on this area of Igboland, and MSU helped found the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. So, there's no university on the face of this planet that could fit my needs any better than MSU," said Achebe.

"I wanted to train a new generation of Africanists—to work with Ph.D. students and place them in jobs. When I came here in 2005, the African History program was not ranked. A few years later we rebuilt the program, and moved up in rank to number three, and then just last year we became number one. It is such a fabulous feeling," said Achebe. "With all of the classes I teach, with all of the interactions that I have with students that I encounter, my aim is very simple: to make students understand that Africans, with all of their imperfections, are human beings, who are more like them than not. If my American students are saying 'oh I get that, they're not so different, I see why Africans do A, B or C—I can relate to that,' then my job has been done.

Field Work

Nwando Achebe often discusses her father's book, Things Fall Apart, incorporating discussion about gender: "I'm a historian, therefore I teach the novel as history."

It took Achebe fifteen years to research her second book, The Female King of Colonial Nigeria: Ahebi Ugbabe (2011). The work began during her dissertation years.

"This female king was the reason I decided to do my research on this particular group of Igbo people. Igbo women are some of the most important African women on the continent. One can argue that it is Igbo women, because of their 1929 ogu umunwanyi or women's war, that put African women on the intellectual map," said Achebe.

Igbos consider themselves more of a democracy, so discovering a female king, not even a queen, was fascinating for Achebe. After reading an anthropologist's description, she was intrigued by this unusual happening in that community and decided to pursue it.

According to Achebe, sex and gender are not the same thing, and they don't coincide. You can be born biologically female but become a man. This is how a female king was not a queen, she became a king.

"The first year that I worked in the community, I went through everything I needed to do in terms of permissions. I was working in a society that was a gerontocracy. You don't just walk in and start asking questions. That is considered rude. So, you have to go to the oldest man and the oldest woman and introduce yourself, tell them what it is that you're doing, and hope they grant you permission to do your research. That's what I have done in all of the communities I've worked in," said Achebe.

"As a people's historian, it is important to me that my oral historian collaborators know that I will represent them the way that they represent themselves."

Different communities call for different approaches to fieldwork. "When you have a dual sex system, you go to male government to gain access to speak with men, and you go to female government to speak with women. In these systems, men take care of what's important to men, and women take care of what's important to women. But in a centralized society, you seek audience with the king or queen. During my actual conversations with my oral history collaborators, I ask for interpretations of their lives, I ask them to share their life histories with me, without interruption. I only interrupt if I don't understand something that they have said. At times like those, I ask, 'what did you mean by what you just said?'—I do this to seek their interpretation of their own realities, so that it is not me assuming that I know what they mean. As a people's historian, it is important to me that my oral historian collaborators know that I will represent them the way that they represent themselves," said Achebe.

Field work proved challenging during her second book.

"Person after person told me that Ahebi Ugbabe grew up in their community and just happened to get lost. How does a 12 or 13-year-old just get lost, I would ask? They had no answer. They simply repeated this telling of history. But then, 2-3 years into my research, the truth finally came out, when I met up with one of the most powerful medicine men in the community. When I asked him the same question that I had asked all my other oral history collaborators, his answer was different. He said, "Really—is that what they're telling you? Of course they're not going to tell you the truth,'" said Achebe. "He then informed me that Ahebi did not get lost, that she ran away because she had been dedicated to a deity in marriage because of a crime that her father committed. This practice is called igo mma ogo—becoming the in-law of a deity; and it is a form of indigenous slavery."

History and "Getting it Right"

Achebe asks oral history collaborators to share their life stories without interruption: "I only interrupt if I don't understand something they have said."

As an oral historian working to "get it right," Achebe acknowledges that scholars come into the research field with their own preconceived perceptions.

One of Achebe's field experiences involved a woman who insisted that Achebe represent her in the right way. "She starts telling me her life story, and everything she knows about what it means to be a woman. What she said totally went against everything I had studied, and everything I knew. I'm sitting there thinking, I'm not going to use this interview because it just doesn't fit with my analysis.

"I would later realize that the reason that I couldn't reconcile what she had just said to me was because I had come into the field with an agenda. However, Madam Obayi forced my hand when she instructed me to turn the tape recorder off and repeat back to her what she had just said. I did just that—parroting back to her all the information that I had heard, but did not believe. Then the most remarkable thing happened: Lady Obayi asked me to turn the tape recorder back on because I had shown her that I would represent her in the book that I was going to write, the way that she represented herself.

"From that experience, that happened early in my fieldwork, I learned an important lesson, that one should not go into the research field with a preconceived agenda," said Achebe. "I think it was in my attempt to right all of those perceived wrongs about African women, that I had gone into the field wanting to correct those images, and present what I deemed a positive perspective of African women.

"We all have bias. But, what we do as feminist oral historians is to acknowledge that bias, and say 'this is who I am, and this is my baggage—good or bad—and the way that I see the world affects—for better or worse—the way that I understand the world.' I have taken myself through this honest self-naming and self-discovery in the methodology chapters of both my books. I have also written an article on my field experience in the Journal of Women's History," said Achebe.

"I pride myself on writing in an accessible style so that the people that I am writing about can read and understand the history before them, and see themselves in the stories."

It took her about a year to write the second book. "When I was writing, I kept hearing my father's voice telling me to never lose sight of the story that I was trying to tell," said Achebe. "I pride myself on writing in an accessible style so that the people that I am writing about can read and understand the history before them, and see themselves in the stories."

Ongoing Work and Future Plans

Achebe has a great deal in the pipeline. In addition to her faculty responsibilities and research, she devotes time to speaking to young people who study Things Fall Apart in school.

"This is something that I started doing in the early 1990s. And I have had a remarkable relationship with several high schools. In many instances, the principal of the school extends the invitation to me to come speak to his/her students. In some instances, regularly scheduled classes are cancelled, so that all students and faculty can listen to my presentation," said Achebe. "Talking about Things Fall Apart is something that I am excited to do; to catch those students early and introduce them to the world of the novel. One of my very favorite things to do with the students is to talk about gender in Things Fall Apart. As you know, I'm not a literature person, I'm a historian. Therefore, I teach the novel as history."

She is part of a team of scholars that compiled a history textbook for high school students in West Africa, replacing textbooks and syllabi that were created in the 1950s. She just finished A Companion to African History with William Worger and Charles Ambler, and is co-editing Holding the World Together: African Women in Changing Perspective with Claire Robertson, which is scheduled for release in mid-2019. She has also just completed the forthcoming (2019) University of Ohio Press book Female Monarchs and Merchant Queens.

Achebe is deeply involved in the Journal of West African History, a journal published by Michigan State University Press, for which she is founding-editor-in-chief. It is an interdisciplinary peer-reviewed research journal focused on providing a forum for serious scholarship and debate on a number of topics pertaining to West African history.

Achebe is equally passionate about encouraging other African writers. She worked with Gabe Dotto, director of the MSU Press, to arrange copy editing support for African based scholars who lack strong writing skills. "Sometimes because these African born scholars are writing in a language that is not their mother tongue, the articles that they submit to my journal do not meet our quality requirement, and therefore are outrightly rejected," said Achebe. "I arranged for extra copy editing of materials sent in from Africa that have potential. I also started a mentorship program for African based scholars—ours is perhaps the only journal published by a university press that has this program for African born scholars. It was important for me to create it, to give these scholars that little boost. Being able to mentor an African scholar from a rough start to a powerful finish, and to provide an outlet for their work, are the things that make me happy. Because for me, that's giving back to a continent that's given me so much."

Africa and the World

What does Nwando Achebe want everyone to know? "Africa is not a monolith. It is the second largest continent with more than 3,000 different nations of people that speak different languages and have different cultures. It is a very complex continent. Its natural beauty and the hospitality of its peoples remain unsurpassed. For those of us that teach about, or do research on Africa, the objective should be to present Africa in its complexity—highlighting its challenges, but also its achievements. This is the way that Africans see themselves; this is the way that they would present themselves. If we do that, I think, we have done a lot."

Source

- Kinsman, M. (1983). "Beasts of burden": The subordination of Southern Tswana women, ca. 1800-1840. Journal of Southern African Studies, 10(1), 39-54. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03057078308708066 Back to Article

- swahiliproverbs.afrst.illinois.edu/experience.html Back to Article

- Written by Carla Hills, University Outreach and Engagement

- Photographs courtesy of Nwando Achebe and Paul Phipps, University Outreach and Engagement

- Pottery piece and photo courtesy of the MSU Museum.