Rebuilding Flint's Future: The MSU-Hurley Children's Hospital Pediatric Public Health Initiative

- Mona Hanna-Attisha

- Associate Professor

- Department of Pediatrics and Human Development, College of Human Medicine

- Director, MSU–Hurley Children's Hospital Pediatric Public Health Initiative

- Director, Pediatric Residency Program, Hurley Children's Hospital

Mona Hanna-Attisha dialogues with a four-year-old Flint resident.

The Michigan State University–Hurley Children's Hospital Pediatric Public Health Initiative was established in the wake of the Flint water crisis that emerged three years ago. Lead and other contaminants found in the water triggered a public health emergency that drew media attention from around the world.

Mona Hanna-Attisha, associate professor of pediatrics and human development in the College of Human Medicine, is now regarded as a champion public health advocate for Flint's children and their families because of her dogged pursuit of answers about lead in the water and what it was doing to those in the community. Widely and affectionately known as "Dr. Mona," she has accepted a new challenge to lead an initiative that establishes interventions for prenatal through teen years. It is hoped that the tools developed by the initiative will mitigate children's exposure to the contaminated water supply.

Mona Hanna-Attisha, associate professor of pediatrics and human development in the College of Human Medicine, is now regarded as a champion public health advocate for Flint's children and their families because of her dogged pursuit of answers about lead in the water and what it was doing to those in the community. Widely and affectionately known as "Dr. Mona," she has accepted a new challenge to lead an initiative that establishes interventions for prenatal through teen years. It is hoped that the tools developed by the initiative will mitigate children's exposure to the contaminated water supply.

Crisis in the Making

Citizens in the United States have enjoyed reliable access to sanitary water for more than 150 years. Since the enactment of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1848, there have been relatively few concerns about U.S. drinking water, especially in Michigan where 3,000 miles of shoreline frame the Great Lakes.

In April 2014, Flint's water supply was switched from the Detroit system to the Flint River in a management decision aimed at saving costs. Flint had come under emergency management from the state of Michigan in 2011 due to an estimated $25 million budget deficit. Flint residents began to complain of discolored and foul-tasting tap water after the switch, and then detrimental health symptoms began to emerge in children and adults. As tension rose in the community, people sought information and demanded action.

After Hanna-Attisha became aware of the potential lead exposure in the water, she conducted an analysis measuring children's blood lead levels before and after the water switch. On September 24, 2015, she released a study showing that children younger than five years of age who were tested had lead levels in their blood that were nearly double after the 2014 change from Lake Huron to the Flint River as their water supply. The percentage of children with elevated blood lead levels increased after the water source change.

Investigations determined that state and federal water quality measures were not implemented to treat pipe corrosion, causing poisonous levels of lead and other contaminants to leach into the water supply—water that Flint residents drank, cooked with, and bathed in.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) predicted in July 2016 that approximately 99,000 Flint residents were affected. Of those, approximately 7,000 children were initially tested. Since that time, unfolding events have brought issues to the forefront that involve health, governmental management, environmental science, social justice, and civil and criminal laws.

The MSU–Hurley Children's Hospital Pediatric Public Health Initiative (PPHI)

The federal government declared the water crisis in Flint to be an emergency in January 2016, formally acknowledging that Flint drinking water posed a threat to public health. Hanna-Attisha and representatives from MSU and Hurley Children's Hospital had already been at work with community partners since late 2015 to develop a framework for addressing children's needs, both during the current situation and in the future. It was officially submitted via the CDC Emergency Operations Center (EOC).

The MSU–Hurley Children's Hospital Pediatric Public Health Initiative encourages Flint families to eat healthy. The Flint Farmers Market features fresh fruits, vegetables, and locally-sourced products.

The initiative brings together experts in pediatrics, child development, epidemiology, nutrition, toxicology, geography, education, psychology, and community and workforce development. The MSU College of Human Medicine, MSU Extension, MSU College of Education, several other MSU faculty and specialists spanning the University, Hurley Hospital, and various community stakeholders joined together to create the initiative.

"It's really a crisis on top of a crisis," said Hanna-Attisha. "Since the 1970s and early 1980s Flint has experienced hardship—in some cases extreme hardship—caused by unemployment, poverty, and crime."

Much of the work began with a focus on developing scientific metrics and evaluations for long-term interventions and assistance. One critical component is the Flint Water Crisis Registry, a public health effort that will identify, track, and support Flint water crisis victims.

The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services awarded a one-year grant of $500,000 during the first part of 2017 for planning the registry. In March 2017, Nicole Jones was named the registry's director. Jones is a lifelong resident of Genesee County who received her Ph.D. in epidemiology and postdoctoral training in perinatal epidemiology at Michigan State University. Prior to her appointment, she was part of the team working with Hanna-Attisha to lay the groundwork for the registry.

In August 2017 it was announced that legislation championed by Michigan's congressional leaders the previous year produced a four-year, $14.4 million grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to help build and maintain the registry. The first installment is $3.2 million and will go toward establishing the registry. Enrollment is expected to begin in early 2018.

Prenatal screenings play an integral role in pediatric health.

"We begin with prenatal care and follow these children. We know that childbearing-age women who consumed the Flint water may not be testing high right now, but the lead can be absorbed into bones and leach out again when their body experiences stressors later on. Pregnancy can be one of those stressors, and then it is potentially passed on to their baby," said Hanna-Attisha.

The foundation for the initiative is the College of Human Medicine's 48-year-plus medical education collaboration with Hurley Medical Center, which leverages MSU's 2014 Flint expansion of its Division of Public Health. The collaboration is designed to bring new public health researchers to Flint to study the community's most pressing public health needs.

The initiative's design is based on a new eco-bio-developmental model of human health and disease. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, scientific advances have brought about an integrated framework that addresses both early social and environmental experiences (ecology), and genetic predispositions (biology). Those factors influence the development of adaptive behaviors, learning capacities, lifelong physical and mental health, and future economic productivity. This means that early childhood experiences build a strong foundation for a lifetime of learning, health behaviors, and wellness.

"I'm a doctor and I think health care is obviously important, but I think the real need is for early education. A child's brain doubles in size from zero to two, and when their developing brain is affected like it is with the lead and other contaminants in the water, then it impacts the entire trajectory of learning. We need this pediatric public health initiative to offer all kinds of interventions," said Hanna-Attisha.

Sheldon Neeley represents the 34th State House District, which includes most of the city of Flint. He was elected to the Legislature in 2014, after serving nine years on the Flint City Council, Sixth Ward.

"Our citizens are traumatized, and I'm focused on recovery dollars that can provide the necessary tools for short, medium, and long-term assistance," said Representative Neeley.

Neeley is supportive of the collaborative efforts put forth by MSU and a variety of community stakeholders. He is a strong supporter of higher education and the role it plays working in the Flint community.

"We have Mott Community College, Kettering University, Michigan State University, and the University of Michigan— that's more students per capita than any other Michigan city. They are invested in Flint, and they have been here with us. Higher education has a more cerebral approach to solutions. They see the whole dynamic and can address problems holistically rather than looking out for one dimension," said Neeley.

According to Neeley, the academic approach will benefit his constituents and others affected by the water crisis: "Working together will be the key to success. Partnerships are the key to success."

Five work teams under the MSU-Hurley Children's Hospital Pediatric Public Health Initiative

- Child Health and Development

- Nutrition

- Exposure Assessment

- Health Informatics

- Child Health Policy and Advocacy

These teams work closely with the PPHI Parent Partner Group and the PPHI Flint Kids Advisory Group.

A blend of governmental and philanthropic sources now support many of the recommended interventions, including:

- Expanded maternal-infant support programs

- Universal home-based early Intervention

- A new high quality early education center, with another opening in 2018

- Family and parenting support programs

- Massive investment in early literacy and two-generation literacy initiatives

- Universal preschool

- School health services

- Mindfulness programming

- Breastfeeding support

- Nutrition prescriptions

- WIC colocation with primary-care mobile grocery stores

- Trauma-informed care

- Health care expansion via Medicaid waiver

Hanna-Attisha acknowledges that the scope of the effort has its challenges, including how to build, maintain, and manage a database of citizens, and then steering those citizens into interventions that will help address their needs.

"As I've said before, it's like building a plane while you're flying it," said Hanna-Attisha. She stresses that there is a long way to go and this intervention initiative will require years of generational follow-up.

Catholic Charities of Shiawassee and Genesee Counties has a 75-year history in Flint, and their staff members have participated in widespread efforts to meet the challenges produced by the contaminated water.

"We serve 16,000 meals per month. Try making, serving, and cleaning up that much food with bottled water," said Vicky Schultz, president and CEO. "I know there are recommendations for fresher fruits and vegetables, but our budget is stretched with all the extra responsibilities we have encountered in the past three years."

Schultz's staff and volunteers distribute 4,000 cases of water per day, which she says is more than the fire department. They have managed the added responsibilities of unloading, reloading, and delivering water. In addition, they have installed filters, tested water, and monitored water in homes. The need for body and baby wipes soared, along with requests for showers and water bill assistance. All of it was in addition to services for counseling, prevention, and child welfare, soup kitchens, sack lunch programs, foster care, and a community closet. Schultz is aware of the need for both immediate and long-term care due to the water crisis.

"I've been in my current position for 10 years, and I didn't think things could get any more basic for this community. But then the water crisis hit, and things became even more basic," said Schultz.

The initiative's interventions are rolling out while individuals and organizations are still grappling with the day-to-day reality.

"There are trust issues for sure," said Schultz. "So if Mona Hanna-Attisha is leading the initiative then it solves one thing, because the community trusts her."

Hanna-Attisha views the PPHI as an opportunity. "It's an opportunity to recommit to kids and to Flint residents. It's a recommitment on MSU's part, too. Michigan State University has a century-old footprint in this community, and that's a long history of caring about—and working with—the Flint community. We can do this."

Source: Michigan State University, College of Human Medicine. (n.d.). About MSU–Hurley Children's Hospital Pediatric Public Health Initiative. Retrieved from http://humanmedicine.msu.edu/pphi/About.htm.

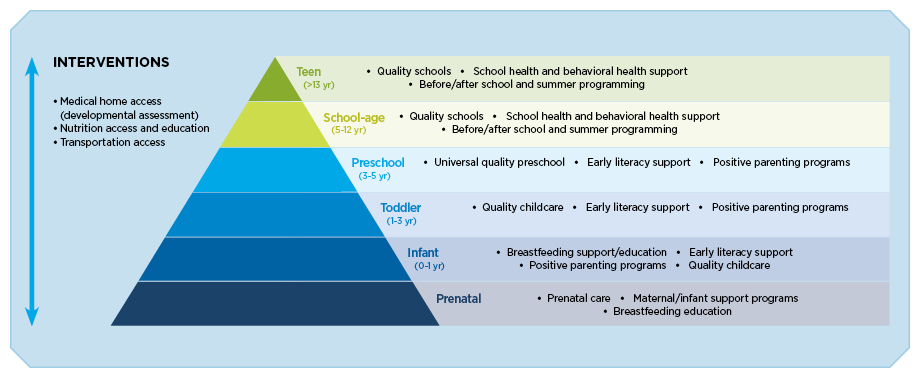

Interventions

- Medical home access (developmental assessment)

- Nutrition access and education

- Transportation access

A framework for mitigating interventions was developed with community partners in late 2015 and was officially submitted via the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) after declaration of the federal emergency status (January 2016).

| Teen (>13 yr)

|

- Quality schools

- School health and behavioral health support

- Before/after school and summer programming

|

| School-age (5-12 yr)

|

- Quality schools

- School health and behavioral health support

- Before/after school and summer programming

|

| Preschool (3-5 yr)

|

- Universal quality preschool

- Early literacy support

- Positive parenting programs

|

| Toddler (1-3 yr)

|

- Quality childcare

- Early literacy support

- Positive parenting programs

|

| Infant (0-1 yr)

|

- Breastfeeding support/education

- Early literacy support

- Positive parenting programs

- Quality childcare

|

| Prenatal

|

- Prenatal care

- Maternal/infant support programs

- Breastfeeding education

|

- Written by Carla Hills, University Outreach and Engagement