Building Walkable Communities

- Igor Z. Vojnovic

- Department of Geography

- College of Social Science

Students in Igor Vojnovic's Metropolitan Environments class employ designs that encourage non-motorized travel. They prepared these development proposals pro bono for Lansing- and Detroit-area municipalities. The proposals were presented as 3-D computer-aided design models.

Igor Vojnovic loves living right next to downtown East Lansing. "My wife and I can walk to our favorite restaurants, our bank, and book stores. She walks to work in ten minutes," he said. "It makes a lot of economic and environmental sense."

Dr. Vojnovic heads a $643,000 collaborative study, funded by the National Science Foundation, to pinpoint key factors in mode-of-travel choices. His partners include a multi-university team of geographers, epidemiologists, statisticians, and urban planners, along with the Governor's Council on Physical Fitness, the Michigan Suburbs Alliance, the City of Detroit, Blue Cross Blue Shield, and other agencies.

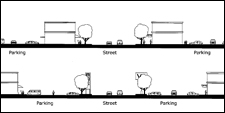

Reducing barriers—minimal setbacks bring people and buildings closer together, facilitate window shopping, improve pedestrian access to buildings, increase street activity, and create a more interesting pedestrian environment.

The research aims to determine how variations in income, race, age, and gender affect travel behavior in six diverse neighborhoods between Detroit and Ann Arbor. "We have a national obesity epidemic," said Vojnovic, "and it's hitting some populations harder than others— African-Americans, Hispanics, the elderly, women. What are some of the variables that influence their commuting decisions?"

The project started on a smaller scale in the Lansing area, with funding from MSU's Land Policy Institute and the Community Vitality Program. The pilot research found that in high density, mixed use neighborhoods more residents walked to their work, shopping, and leisure activities.

Interestingly, although residents in the lower income Lansing neighborhoods lived further from these destinations, they still walked proportionately more. "We hypothesized that their reliance on walking and biking might simply be a result of having less access to cars compared to households in wealthier neighborhoods," said Vojnovic. "Another revealing aspect of the Lansing study was that fewer women participated in physical activity, whether moderate or vigorous, than men."

Of course community design isn't the whole health picture, "but walking to work and other daily activities can be part of it," he said. "We know that these choices are culturally based. People have to value exercise and health. Physical environments in themselves do not determine behavior; however, they can be supportive or inhibitive of making healthy choices."

Engagement is embedded in scholarship

| Region

|

Work trips

|

Avoid a dispersed metropolis with no clear core. Public transit can do a better job of serving a high-density area with employment and population concentrated at the center.

|

| Subregion (within-city)

|

Personal travel (errands, recreation)

|

Localize the errands. Reduce the distance between destinations to make trips shorter on average.

|

| Local (city block)

|

Streetscape, pedestrian safety, and distance

|

Give pedestrians more streetscape texture. They travel at lower speeds, so it's more relevant to them.

|

- Written by Linda Chapel Jackson, University Outreach and Engagement