The Citing Slavery Project:

Documenting the Continuing Influence of Slavery on U.S. Law

- Justin Simard, J.D., Ph.D.

- Associate Professor

- College of Law

Project Overview

- The Citing Slavery Project documents cases involving enslaved people and the modern cases that continue to cite them as precedent.

- Justin Simard, an associate professor in the MSU College of Law, and his students have visited high schools in Ferndale and Detroit as part of educational outreach.

Products/Outcomes

- A website, citingslavery.orgExternal link - opens in new window, that includes a database of approximately 14,000 cases involving enslaved people and modern cases that cite them.

- Lesson plans focusing on precedent that can be made available to high school teachers and incorporated into existing curriculum.

- Relationship-building between MSU law students and professors and under-represented high school students with a goal of diversifying the legal profession.

- Outreach to the legal community.

Partners

- Taylor Sastre, Advanced Placement Government teacher, Cass Technical High School

- Ferndale High School (2022–2023)

Form(s) of Engagement

- Community-Engaged Teaching and Learning

- Community-Engaged Research

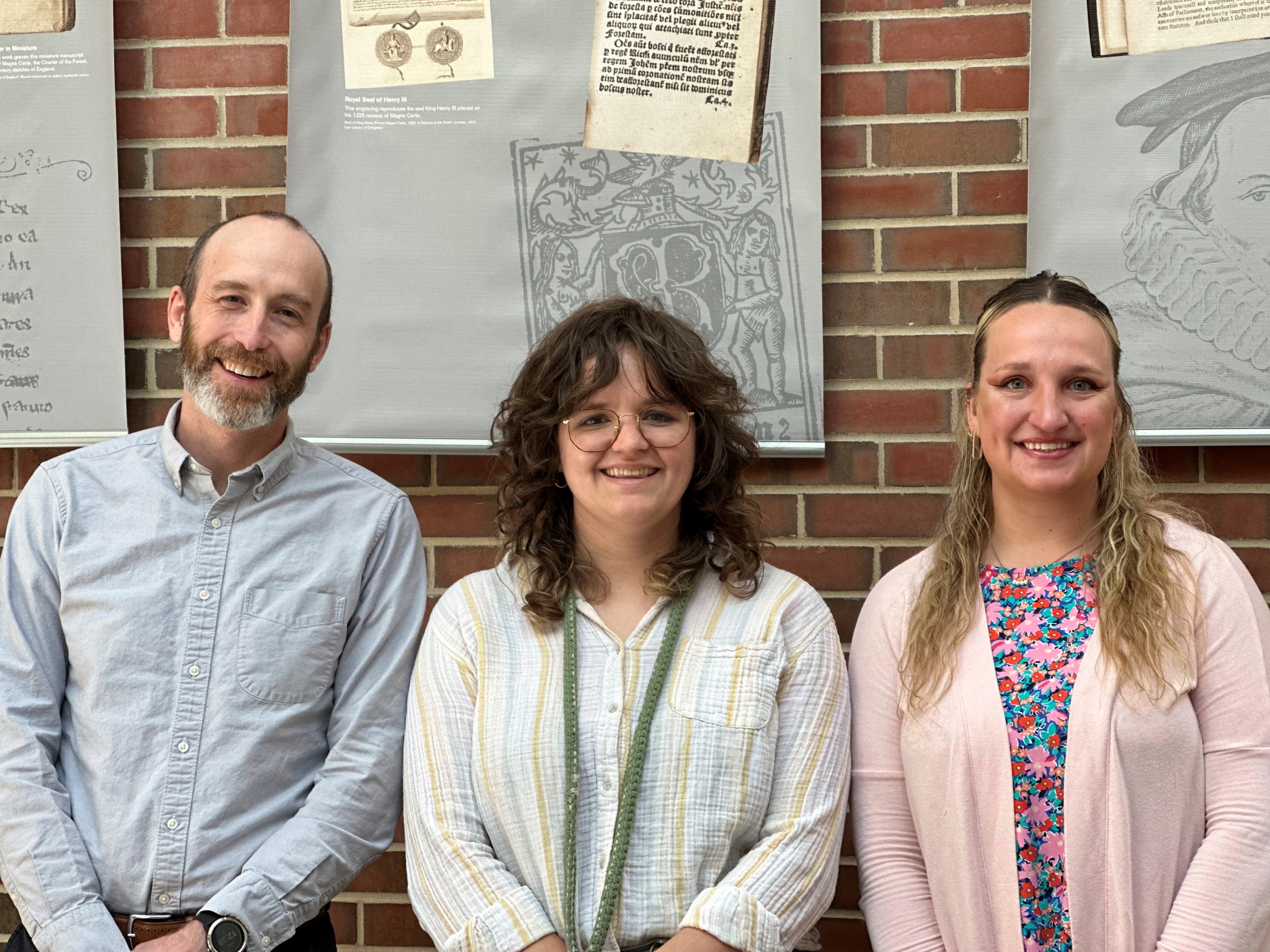

Associate Professor Justin Simard is joined by Cass Technical High School teacher Taylor Sastre and law student Hannah Gates at the MSU College of Law. Sastre and her students met the dean and other faculty members during a campus visit in April.

As they deciphered the antiquated language of 19th-century legal cases involving slavery, students at Cass Technical High School in Detroit discovered a troubling narrative. Lawyers and judges often treated enslaved people as property, considering those who were ill or injured “damaged goods.”

Worse, they learned, courts continue to cite these cases as “good law” well into the 21st century. “It’s disheartening when I think about the fact that our country has come so far and African Americans have fought for our civil rights,” said Jessica McCloud, 18. “It’s so hard to see slaves treated as objects. More people should know about it.”

McCloud and her Advanced Placement Government classmates are helping raise awareness of these cases—and the human stories of the enslaved people at the center of them—by participating in MSU’s Citing Slavery Project.

Founded by Justin Simard, an associate professor with the MSU College of Law, the project has documented upwards of 14,000 appellate cases involving slavery. Simard and a team of law students have created a websiteExternal link - opens in new window that lists them along with the 45,000 cases that cite them.

“The goal of the Citing Slavery Project is to document the continuing influence of slavery in American law,” Simard said. “The legal profession was complicit in slavery. Judges still cite cases involving enslaved people as good law.”

An Accidental Discovery

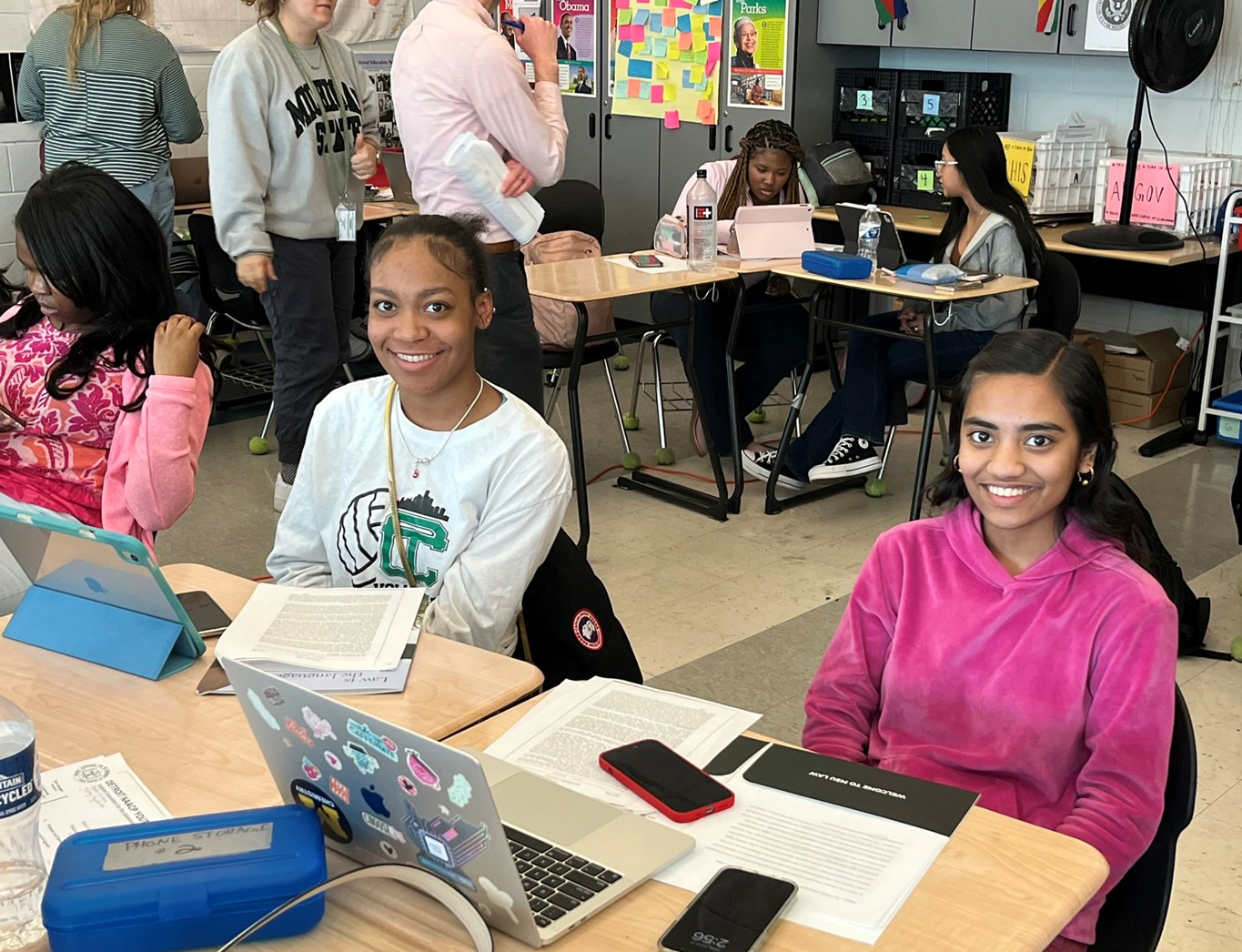

Cass Technical High School seniors Jesssica McCloud and Aditi Roy said they were surprised and disappointed to learn that cases involving enslaved people are still cited as legal precendent today.

Simard stumbled upon the modern-day citation of slavery cases when he was working toward his Ph.D. in history. His dissertation focused on the 19th-century commercial work of lawyers involving slaveowners. He noticed that a case involving an enslaved person was cited just a few years ago.

“It was shocking to me,” he recalls. “I just couldn’t believe it. [The case] was cited without recognizing it involved enslaved people. It was treated just like a normal case.”

Initially he thought he’d find three of four cases. But he kept digging and found hundreds.

Simard wrote an articleExternal link - opens in new window on his findings entitled “Citing Slavery” for the Stanford Law Review. He came to MSU in 2020. Following a seminar on the law of slavery, Simard asked if any of his students wanted to help collect more cases.

Starting with 300 cases citing slavery that Simard had already discovered, he and the students created a website. Today the database includes 12,000 cases, and about 3,000 more will be added this summer.

Simard estimates that 18 percent of all American cases are within two steps of a case involving an enslaved person. That means they either cite a case directly or cite one that cites one.

Reckoning with Past and Present Harms

Documenting the staggering number of these cases challenges the legal profession to reckon with its role in shaping and upholding slavery, Simard said.

“But there is also the harm of the continued use of this law,” he said. “By continuing to treat these cases like regular law, people are not only citing the dehumanization of people but also re-dehumanizing the people that were involved,” he said.

One example is Tire Shredders, Inc. v. ERM-Northern Central, Inc. (1999), decided by the Tennessee Court of Appeals. In discussing whether to award damages to the owner of a damaged tire shredding machine, the court cites Johnson v. Perry, an 1841 case that awarded damages to the owner of an enslaved person named David who suffered a broken leg in an altercation involving two defendants.

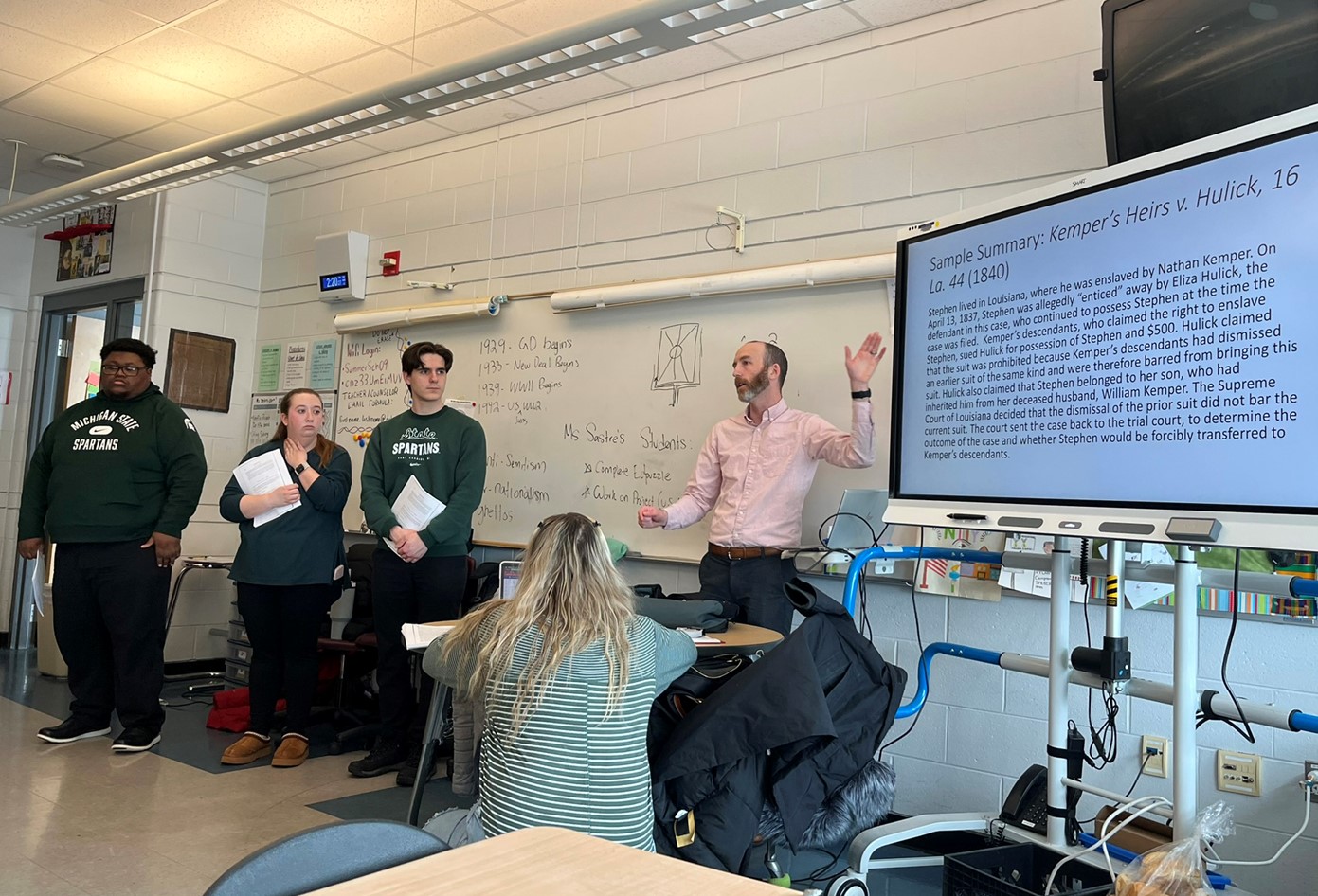

Professor Justin Simard describes a case summary as students Kenneth Ayers and Caitlin Butcher, College of Law, and Jesse Doolin, pre-law, look on.

The recent case equates property damage—to the machine—to injuries to a human being. “The modern case is talking about this slave case as if it’s just a normal case,” said Simard. “Even this modern court is continuing to treat enslaved people like property.”

Simard and his law students have sought to increase awareness of this practice through outreach to the legal community. The team has presented its findings to law students, lawyers, and judges. Last fall, the Oregon Court of Appeals invited them to give a presentation.

Additionally, the team successfully lobbied the editors of the Bluebook, a style guide for the legal citation system, to acknowledge the citation of cases involving slavery. Those citations will now include a parenthetical note (enslaved person at issue). The team would like to see a similar acknowledgement added to commercial legal databases.

Educational Outreach Program

These efforts make progress toward a key goal of the Citing Slavery Project, which is “to get the legal profession to acknowledge and atone for the role that it played in slavery,” Simard said. However, “talking to lawyers is not enough,” he said.

By reaching out to high school students, the team hopes to change the profession from the inside out by encouraging individuals from underrepresented communities to become lawyers. “The goal is to diversify the legal community and to encourage young people to feel comfortable thinking about and talking about the law,” Simard said.

He credits MSU law graduate Taylor Hall with the idea. Hall, who graduated last spring, reached out to her alma mater, Ferndale High School, in 2022. With funding from the Engagement Scholarship ConsortiumExternal link - opens in new window, Simard, Hall, and several other law students gave presentations to students, who also visited MSU to meet other students and professors.

Hannah Gates, a second-year law student, volunteered to run the program this past academic year. The partnership with Cass Technical High School came about when AP Government teacher Taylor Sastre heard a story about the Citing Slavery Project on National Public Radio last summer.

Sastre reached out to Simard and the team via social media. MSU Law and Cass Tech already have a longstanding relationship that includes an annual presentation on First Amendment rights.

Gates, who has a master’s in educational leadership and policy, developed a curriculum focusing on precedent. “Citing Slavery shows and exemplifies how precedent is being used in negative ways,” she said. “Students can start thinking critically about how laws are influenced by negative precedents.”

A former Detroit elementary school teacher, Gates credits Sastre for ensuring the three-session unit would be age-appropriate, relevant, and fit seamlessly into the AP Government curriculum.

Sastre’s participation has been critical to the project, Simard said. “We didn’t want to just sort of parachute in . . . She reviewed the lesson plans, helped fine-tune it, and provided advice to ensure that the unit would connect with what the students were learning.”

Empowering Students to Make Change

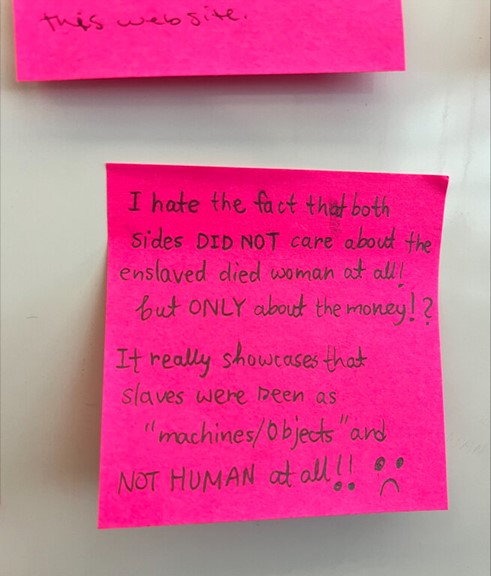

Cass Technical High School students used post-it notes to share their reactions to learning about the modern-day citations of cases involving enslaved people.

In March, Simard, Gates, and students drove from MSU to Cass Tech on Fridays. At the first session, they presented an overview of the Citing Slavery Project and showed the students a Bill of Sale, an artifact that shows in concrete detail the way enslaved people were treated as property.

The Tire Shredders case is a powerful example of that, Gates said. “The kids were really taken aback by that—about how a person is being compared to a machine. They wrote that they were disgusted, they were horrified.”

On their final visit, Simard invited the Cass Tech students to write summaries of cases that cite enslaved people. “I didn’t want to just dump this on them,” he said. “We’re coming in and saying the legal system has problems. I wanted to give them a chance to be part of helping fix it.”

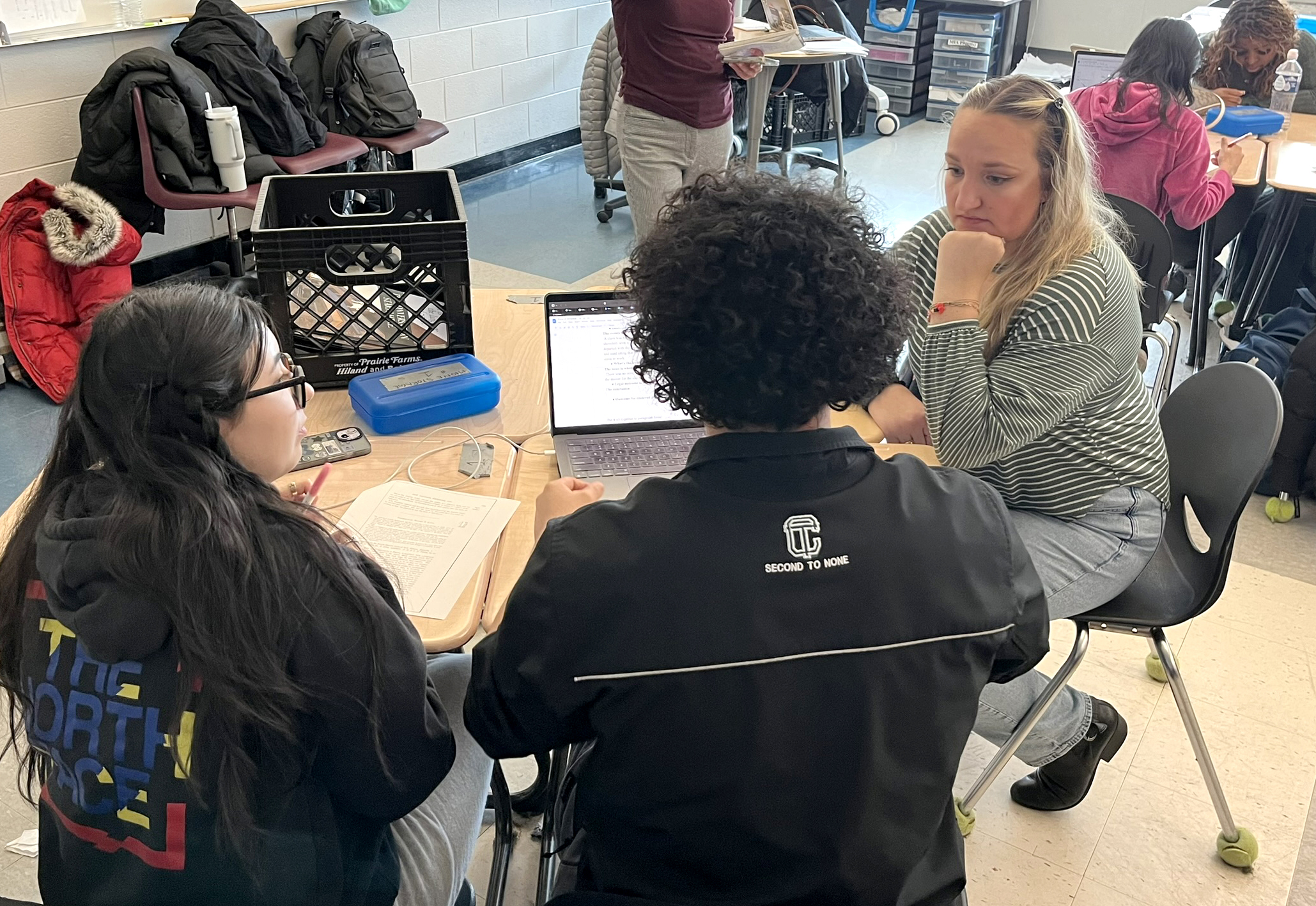

Students worked in pairs and submitted their summaries to Gates, who will upload them to the Citing Slavery website and credit the students. “You’re helping us make our website more accessible to other high school students or undergraduates,” Simard told the students.

The benefits go both ways. Interacting with Simard and the MSU law students energized her students, Sastre said. “It really opens doors to what’s possible,” she said. “I think a lot of times kids feel really disempowered by the legal system, especially when we tell them these are all the ways that historically the legal system has hurt communities of color and how things have been done to them.

“When they see there are ways we can dismantle and make changes it can be a way of empowering kids,” she said, adding that she would not be surprised if some of her students choose to go to law school after participating.

Kenneth Ayers, a second-year law student at MSU and project volunteer, said he was impressed with the students. “To see high school age children be able to decipher these cases, feel their emotions, and be able to articulate their points of view . . . It was inspiring to me that young people already are ready to make a change.”

Next Steps

MSU law student Hannah Gates helps students draft case summaries that will be added to the Citing Slavery Project website.

Once the database is complete, the next step will be to add more case summaries. Simard is also considering writing an article that incorporates the students’ summaries and lists them as co-authors. The team would also like to add additional details to help genealogists locate their ancestors.

Next year, the Citing Slavery Project may expand its educational outreach program to include Lansing Public Schools. They would also like to make the lesson plans available online to other school districts.

“Education about slavery is under attack throughout the country,” Simard said, noting that the facts surrounding the cases and citations are indisputable. Making lesson plans available to teachers would allow them to easily incorporate them into their curriculum.

More generally, he would like to see the legal profession as a whole “acknowledge the role it played in slavery.” That may include installations at courthouses or acknowledgments on their websites, for example.

“There’s so much work to be done,” said Simard. “It’s exciting but also scary to see how much more we have to do to get people to understand the importance of these cases and their influence on the law.”

- Written by Patricia Mish, University Outreach and Engagement

- Photographs by Emily Springer