Tipping Points to Leverage Points: Modeling Flint's Food Systems

- Steven Gray, Ph.D.

- Associate Professor, Department of Community Sustainability

- College of Agriculture and Natural Resources

Project Overview

- Utilizing participatory modeling methods, the Leverage Points Project draws together multiple food system stakeholders in Flint to address food access issues in the city.

- By leveraging the knowledge and expertise of many individuals from multiple sectors of the food system, problems, goals, and solutions are defined, discussed, developed, and applied in democratic and equitable ways so that all sectors and residents are benefitted.

Products/Outcomes

- Increasing understanding of the Flint food system so that complementary resources can be discovered and leveraged together

- Increasing funding of grants for food relief programs

- Increasing dispersion of project data via the project website

- Increasing promotion of social justice and equity in Flint's food systems through a democratic modeling process

- Proposing actions to alleviate obstacles, such as lack of transportation

- Increasing public awareness through a community art project and through sharing research results at community events

- Submitting peer-reviewed journal articles

- Creating publications to help inform community and policy leaders

Partners

- Payam Aminpour, Department of Community Sustainability

- Robert Brown, Center for Community and Economic Development

- Samantha Farah, Crim Fitness Foundation

- Jennifer Hodbod, Co-PI, Department of Community Sustainability

- Sandra Jones, R.L. Jones Outreach Center

- Kent Key, Office of Community Scholars and Partnerships

- Carissa Knox, doctoral student, University of Michigan

- Maria Lopez, Co-PI, Department of Community Sustainability

- Kelly McClelland, Edible Flint

- Miles McNall, Office for Public Engagement and Scholarship

- Damon Ross, Community Foundation of Greater Flint

- Kara Ross, Food Bank of Eastern Michigan

- Richard Sadler, Division of Public Health, College of Human Medicine

- Joe Schipani, Foundation for Food and Agricultural Research

- Laura Schmitt-Olabisi, Co-PI, Department of Community Sustainability

- Renee V. Wallace, Doers Edge LLC and FoodPLUS Detroit

- Chelsea Wentworth, Department of Community Sustainability

- MSU Student Researchers: Rafael Cavalcanti Lembi, Livy Drexler, Johnny Musumbu, Gulraiz Sufyan, Mahdi Zareei

Form(s) of Engagement

- Community-Engaged Research

Damon Ross, program officer at the Community Foundation of Greater Flint, and Lottie Ferguson, chief resilience officer for the City of Flint, network at a Flint Leverage Points Project community event.

Food agency—the ability to choose and acquire food that we like and that is healthy—is something many take for granted. But for some, enjoying a variety of food options may not be so easy. Lack of access, availability, resources, or transportation can cause some city residents to experience "food apartheid," a situation in which they are entrapped by dependence on emergency or supplemental food systems. For many urban areas, food access is an ongoing problem hovering at a tipping point.

Many local Flint experts, residents, and stakeholders are collaborating with a group of MSU researchers, led by Steven Gray, associate professor with the Department of Community Sustainability (CSUS), to discuss and model the city's food systems.

With funding from a Tipping Points Program grant from the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research (FFAR) Feeding America Program, Gray and his partners are using participatory modeling methods to draw on as many voices and perspectives as possible to address food access issues in Flint.

Because urban food systems are large, complex, and often poorly understood, according to Gray, there is no single person who alone can understand how the entire Flint food system works. And often, there's a disconnect between groups that are so busy managing their own corner of the food system, they may not know what other groups are doing.

"So we have to talk to people from the emergency food sector, from the supplemental food sector, from the retail sector, people who are in governance at the city level in Flint, neighborhood community organizers," said Gray. "They all hold a different piece of the puzzle of how the food system works."

Participatory Modeling

The Flint Photo Project, a component of the Leverage Points Project, utilized participatory data collection that helped the project team understand how Flint residents navigate the food system. The resident who submitted this photo said: "I have a neighbor who is elderly but cares for his 100-year-old mother. I try to take a box of healthy fresh food to them at least once a week to ease their need to go out."

Gray, who started his career as an ecologist working in marine fisheries in the mid-Atlantic, attended numerous fisheries meetings along with other scientists, commercial fishermen, and environmental groups. He was frequently surprised by the amount of miscommunication that occurred.

"The problems weren't about the science; they were really about how the science integrates into stakeholders' interests and is put into practice on the ground," said Gray. "That seemed to be a larger issue. So I've transitioned from doing marine science into doing more about how stakeholders can be involved both in the process of decision-making and the creation of science."

In 2011, Gray and an interdisciplinary team of collaborators developed Mental Modeler, a fuzzy-logic cognitive mapping web application that allows groups of users to draw upon the expertise of each individual to collaboratively make decisions, and then represent and test their assumptions in real time. The application, funded by the USDA and National Science Foundation, is easy to use and freely available, and has been utilized all over the world in vastly diverse scenarios, such as modeling bushmeat trade dynamics in Tanzania and adapting to coastal climate change in Ireland.

Using methods of participatory modeling allows all project partners to bring their expertise to collectively define and understand the nature of the problem and engage in democratic deliberation about the problem so they can be fully informed to make the best decisions possible about how to move forward and implement policies that are equitable for all food system stakeholders in Flint.

"How do the people who live there define the problems, the major impediments and barriers to having a sustainable food system or healthier food system? And how do they define the solutions? Those are the leverage points," explained Gray. "So first of all, it's getting an idea of what the structure of the problem is by talking to as many people and as many parts of the food sector as possible, and then taking what we heard back, and saying, 'OK, now what do you guys suggest that we do to push it toward a place where you want it to be?' And that's the Leverage Points project in Flint."

Ensuring Local Objectives are Met

Gray and colleagues from CSUS, MSU Extension, and University Outreach and Engagement, along with a number of students, are working with a dedicated group of local experts who inform the modeling process and meet regularly to keep the process moving forward. These partners include the Community Foundation of Greater Flint and a Community Consultative Panel (CCP), composed of members of a food bank, food pantry, urban agriculture research organization, and Flint Fresh, a food hub that provides access to healthy food.

As the project's process monitor, Renee V. Wallace, executive director of FoodPLUS Detroit, helps ensure that all stages of the research are engaged with, being informed by, and benefiting the community via the Community Consultative Panel. "I look at how we are doing the research, how integrated the research is, and how deeply engaged the community members are in research activities," said Wallace. "I developed a process called 'Pathway to Participation (P2P)' to help ensure that CCP members' voices are being centered throughout the phases of the work to give feedback, to infuse their knowledge about the food system, and to respond to data that's being collected from the broader community. They are the first line of community to engage and benefit from the research process."

To gather initial qualitative data, the partners have conducted focus groups, interviews, and visioning exercises to understand past impacts, current issues, and the future potential of Flint's food system. This qualitative data is being used to create models that will help identify potential leverage points that can be used to move the food system toward a more sustainable state.

Applying Community-Informed Research Findings to Activate Leverage Points

"Our goal is to apply those research findings and support programming and initiatives that are positive local food system interventions," said Damon Ross, program officer at the Community Foundation of Greater Flint (CFGF). "So taking those research findings to Flint stakeholders who work within that food system and who are impacted by the local food system, which would be everyone."

[click to enlarge]

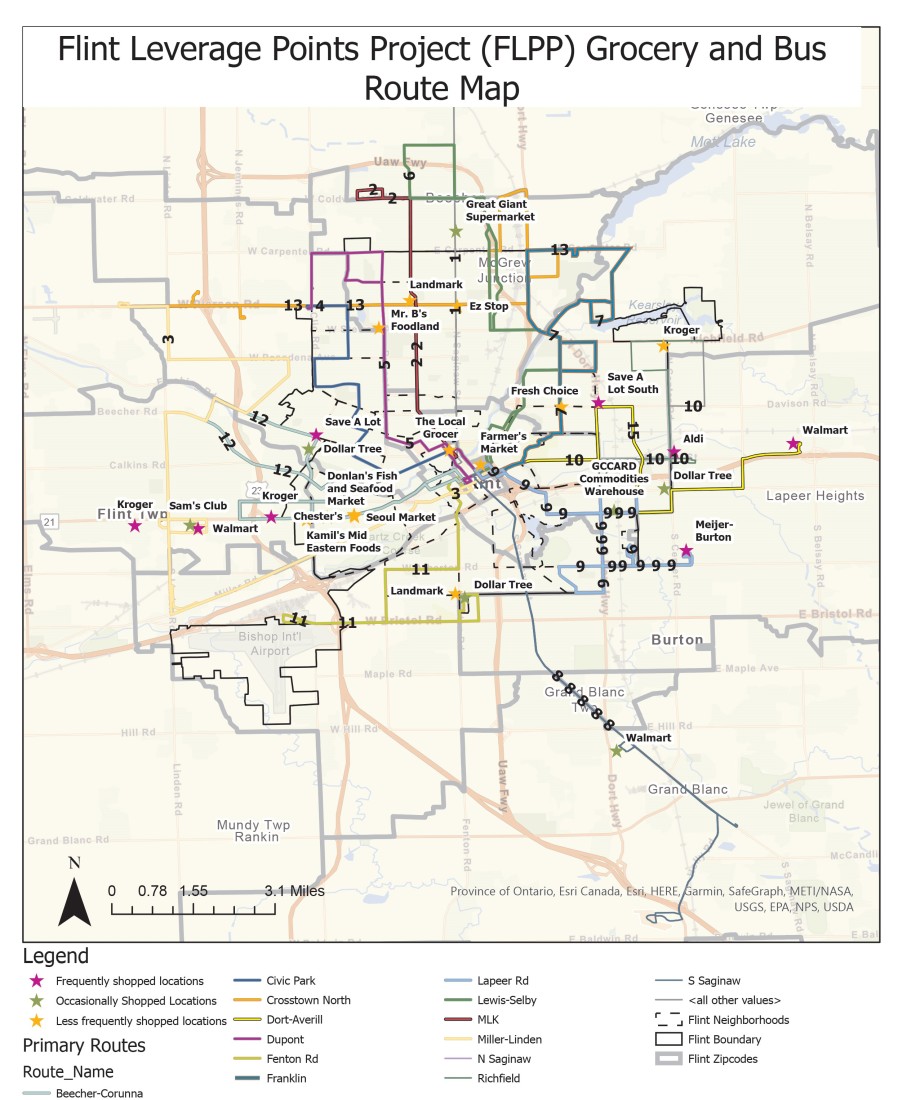

This map of the primary Mass Transportation Authority (MTA) bus routes in 2021, produced by the Flint Leverage Points Project, provides one illustration of how public transportation services grocery locations described by Flint residents. The map illustrates that residents of North Flint must transfer bus lines to reach stores most frequently shopped.

Ross is tasked with grantmaking and community development in the areas of access to healthy foods, recidivism reduction, and neighborhood improvement. He provides guidance to the Leverage Points project as a "persistent voice that represents community," making sure that community members on the CCP are involved in all aspects of the research and that the research is being applied, as well as being a communication "conduit" between community and the academic team.

"CFGF stands in the space that we're connecting, that we're bringing all of those different components together—finding the best possible projects, armed with the outputs that we've gotten from the research project, applying that to the grantmaking, applying that to the proposals, applying that to the programming that our local stakeholders conduct," said Ross.

He describes one output from the research that addresses transportation challenges that some Flint residents face, impacting their ability to access food.

"We've had some projects that were affiliated with the local MTA (Mass Transportation Authority) Rides to Wellness, where community members have a method to get to doctor appointments," he said. "We've kind of modified that with an initiative where folks can actually get their groceries if they have transportation challenges—sort of like an Uber for groceries. There's a ride there; there's a ride back; there's help with your groceries if you have children."

"Imagine how difficult it would be if you had transportation challenges and you're using the bus system," Ross continued. "You have to not only take your family but also what you procure at the grocery store back home. That can be a bit challenging. There is now a mechanism by which you can call up and use MTA, take advantage of that ride share program, and get back and forth to the grocery store. So transportation would have been an obstacle. That programming helps tackle that obstacle, and that's something that came directly from the research."

According to the Flint Leverage Points Project website, other results so far include: funding through CFGF for Urgent Relief Grants for Flint to deliver food to residents' homes during the pandemic; new and bilingual signage for Double Up Food Bucks through CFGF; project data made available on the project website; tools recommended for a community implementation toolkit for applying the project research; a new app developed through Food Fair Network to help disperse information about assistance programs; and faith leaders and others have gained a "big picture" understanding of food inequities in the city.

"There's a lot of really great people doing a lot of really great things around food in Flint. There's no doubt about that," said Gray. "Hopefully, the goal is coordinating some of that effort in a clear direction that is evidence-based and can be community driven. It's informed by what different community stakeholders in Flint are facing and where they want to go."

- Written by Amy Byle, University Outreach and Engagement

- Photographs courtesy of Heike Schwermer, a Flint Photo Project participant, and the Flint Leverage Points Project