Mobile Air Research Lab Assists Abandoned Mine Study in Navajo Nation Communities

- Jack Harkema, D.V.M., Ph.D., D.A.C.V.P., A.T.S.F.

- University Distinguished Professor

- Albert C. and Lois E. Dehn Endowed Chair in Veterinary Medicine

- Director, Laboratory for Environmental and Toxicological Pathology

- Department of Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation

- College of Veterinary Medicine

Project Overview

- Use AirCARE1 lab in Navajo Nation communities to assess airborne exposure to mining dust from 521 uranium mines

- Potential role that dust plays in exacerbating cardiovascular and metabolic diseases

Why This Work Matters

- The prevalence of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases in the Navajo Nation can be exacerbated by particle exposure, such as from airborne mining dust waste. This work assesses the threat posed by open and abandoned uranium mines, so that results can be communicated to regulatory agencies and appropriate action taken.

Products/Outcomes

- Inhalation toxicology studies to determine if airborne particles in the wind-driven dust from abandoned uranium mines are causing a threat to Navajo Nation members

External Partners

- Sadie Bill, Navajo Nation member of the Blue Gap Tachee Chapter, Arizona

- Matthew Campen, Professor, College of Pharmacy, University of New Mexico

MSU Collaborators

- James Wagner, Associate Professor, Department of Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation, College of Veterinary Medicine

- Masako Morishita, Associate Professor, Department of Family Medicine and Director of the MSU Exposure Science Laboratory, College of Human Medicine

- Ryan Lewandowski, Research Assistant, College of Veterinary Medicine

Form(s) of Engagement

- Community-Engaged Research

- Community-based, participatory research

- Community-Engaged Service

Dr. Jack Harkema, on top of one of the AirCARE mobile air research laboratories.

What you can't see can kill you—or at least can make you really sick—including extremely small-diameter particles in the air we breathe. Jack Harkema, University Distinguished Professor of Pathology and Toxicology in MSU's College of Veterinary Medicine, has been studying these tiny airborne particles (particulate matter) for his entire career. His research focuses on how chronic respiratory, cardiovascular, autoimmune, and metabolic diseases affect an individual's susceptibility to the adverse health effects of particulate air pollutants that are emitted into the air from mobile vehicles, industrial sources, natural sources (wind-blown dusts), or chemically generated in the atmosphere.

"Overall I'm really interested in the concept of 'One Health,' looking at how we can best maintain and improve the health of humans, animals, and the environment," said Harkema. "An important component of One Health is the environment that we all live in and its impact on our health and the health of animals. Throughout my professional career, I have been studying the health effects of environmental exposures to airborne toxicants – air pollutants, like ozone and particulate matter."

In 1998, with funding support from an MSU Strategic Partnership Grant and from the Health Effects Institute in Boston, MA, Harkema, along with his University of Michigan collaborator, Dr. Jerry Keeler, designed and had built one of the first mobile air research laboratories (AirCARE1) in the world.

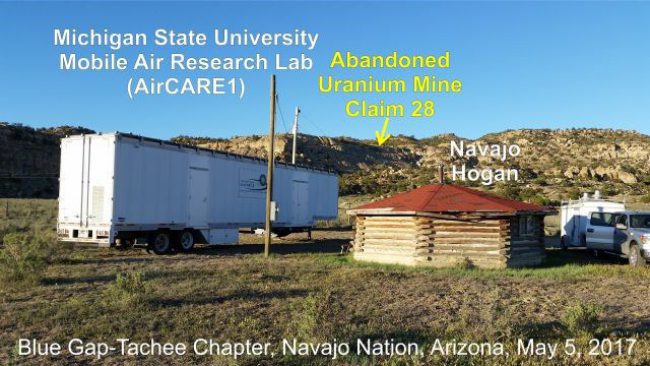

The AirCARE1 Mobile Air Research Laboratory on site at the Navajo Nation Blue Gap Tachee Chapter in Arizona.

AirCARE1 is a 53' semi-trailer converted into a biomedical laboratory that allows scientists to study fine particles in the outdoor air for their potential toxicity and risk to human health. More recently a second similarly designed mobile lab was built (AirCARE2) because of the increased demand for research on the health effects of particulate air pollution. These new environmental and biomedical studies have been funded through federally funded grants from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the National Institutes of Health.

How the Mobile Labs Work

Harkema explains that these labs contain air particle concentrators that draw high volumes of outdoor air by using high-powered vacuum pumps and then filtering and concentrating the very fine airborne particles, 2.5 microns and smaller. These concentrated atmospheric particles are studied to determine their potential impact on human and animal health (particle toxicology).

Harkema and his long-time research colleague, Dr. James Wagner, associate professor in Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation, work with undergraduate and graduate students and postdoctoral fellows in the Laboratory for Environmental and Toxicological Pathology to decipher the toxicity of these "real-world" ambient air particles using specially designed in vivo and in vitro studies. Another research colleague at MSU, Dr. Masako Morishita, associate professor in the Department of Family Medicine and director of the MSU Exposure Science Laboratory, characterizes the physical and chemical makeup of the collected particles (e.g., size, metal content) used in the toxicology studies.

Over the last couple of decades, the AirCARE labs have assisted research all over the country, from large cities like Detroit and Los Angeles to smaller, more rural communities, like Dexter, MI. In 2016, fellow toxicologist from the University of New Mexico, Matthew Campen, approached Harkema about the possibility of using the AirCARE1 lab in Navajo Nation communities in Arizona and New Mexico to assess airborne exposure to mining dust from 521 abandoned and exposed uranium mines, and the potential role that dust plays in exacerbating cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.

Setting up Shop in Navajo Nation

Many Navajo Nation communities are in close proximity to some of these mines, and while important foundational research in the area has looked at contamination of water, very little research has focused on airborne contamination. In an area that frequently experiences windstorms, this might be a cause for concern.

"There is a lot of cardiovascular disease in the Navajo Nation, as well as a lot of metabolic disease, like diabetes. And these chronic diseases can potentially be exacerbated by this unique particle exposure," said Harkema. "We just don't know enough about toxicity of airborne mining dust waste. So, in this case, it's really important to conduct inhalation toxicology studies to determine the effects of breathing this wind-driven dust that is laden with heavy metals and other potentially harmful components."

After receiving a National Institute of Health grant, Harkema's team shipped AirCARE1 out to the Navajo Nation's Blue Gap Tachee Chapter in Northern Arizona, where Campen's team could begin studies on airborne particulate matter coming off the mines.

"Communities are specifically concerned that the dust that blows off of these open mines that haven't been remediated are potentially toxic," said Campen. "So we are borrowing the AirCARE1 trailer from Jack, and we set up shop about a kilometer or so away from the mine site, and we do a lot of toxicology studies. We collect dust samples and send them back up to Masako Morishita, and she does a lot of the metal analysis. She can tell us how much uranium is in all the samples, and other metals as well. So it's been a nice teamwork effort."

Harkema's AirCARE lab manager, Ryan Lewandowski, went out to the Arizona site to help set up the lab, which included designing the installation of an electric pole to establish a power source in the remote area before work could even begin. He was also responsible for training Campen's team in how to run and maintain the particle concentrator. "Our overall goal is to identify if these particles really do cause a potential threat to the people in the Navajo Nation," said Harkema. "And the first step is to identify what's the potential toxicity of these agents to the lungs, heart, and other organs in the body."

Working with the Community

The University of New Mexico project is part of a larger Superfund Research Center grant to look at environmental health disparities research in Native American communities. Teams of researchers have been working with the tribal communities to assess health impacts from water contaminated by the mines, and Campen readily acknowledges his colleagues' efforts in laying the groundwork and establishing trust within the community. "It's important because it takes a long time to develop a relationship," said Campen. "There's no way I could just walk in and start doing stuff. I'm really relying a lot on my colleagues who have already been involved in this work."

Participation of members of the Navajo Nation community has been integral to the success of the study. "We have very close ties with community individuals, and there's always a number of people who work directly with us on the projects, as well as informally supporting the program. And of course, we deal with the governing bodies," said Campen. "It's a bi-directional discussion; we have a number of meetings during the research campaigns where we're sharing data in real time; we host people out to the mobile lab and give them tours. At the last site in Navajo Nation, we did a sheep roast as part of the ceremony to introduce the AirCARE1 mobile lab to the community there."

Sadie Bill is a Navajo Nation member of the Blue Gap Tachee Chapter in Arizona who has been deeply invested in the project. AirCARE1 was placed on a parcel of her land near the mine site, referred to as Claim 28. She said that for years, the tribal community had been trying to find out who was responsible for the mines. "They kept telling us there was no danger to that area," said Ms. Bill. "But in later years, we found out it was contaminated around that area. So we started looking for helpers, and that's how we ended up with the University of New Mexico research team. That's where Matt came in. So they set up the lab, right in the residential area, right below the Claim 28 abandoned uranium mine."

Because she was frequently in that area, Ms. Bill was able to follow what was happening with the research. "Some university students from UNM kept tracking it, and some local people were employed with them so that everyone who wants information, they will give it to them in their native language," said Bill. "And for the community, that was really great for them, because somebody had really cared, and they tried to help them."

According to Campen, initial results look encouraging. "Ultimately, I'm hoping we can put minds at ease about some of the inhalation problems," he said. "I'm reluctant, because I don't know what the results are going to be, but we either see nothing interesting, and that's great for the communities—or we see something that's worrisome and we communicate that in a number of different ways to regulatory agencies, and we see if we can get something done."

For Harkema, this work continues a health-related research focus that spans several decades and involves making connections and building collaborations with experienced scientists all over the country. "It's really about the collaboration—building teams of highly skilled, multifaceted investigators who can work together—so we have the right mix of scientific expertise to conduct meaningful research," said Harkema. "And I really think we're doing studies that are very relevant and translatable for protecting the health of both large and small communities throughout the country, and that, in itself, is very rewarding."

- Written by Amy Byle, University Outreach and Engagement

- Photographs courtesy of MSU College of Veterinary Medicine and MSU Communications and Brand Strategy