The Prison Poetry Zine Project

- Guillermo Delgado, M.F.A.

- Academic Specialist in Community and Socially Engaged Arts

- Residential College in the Arts and Humanities

Project Overview

- Students participate in weekly visits to prisons to engage with incarcerated individuals through poetry and art

Why This Work Matters

- Gives incarcerated individuals an outlet to express thoughts and emotions about their experiences

- Gives students an opportunity to use their art as a vehicle of engagement, while developing an understanding of incarceration in the U.S.

Products/Outcomes

- Poetry classes and slams for incarcerated people

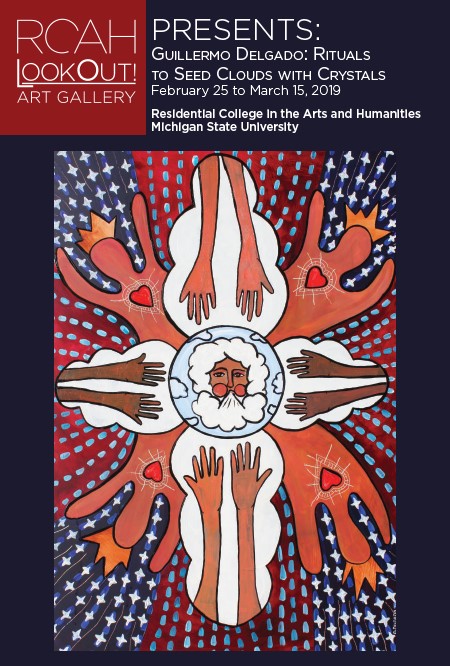

- Immersive exhibit of stories and artwork at the RCAH LookOut! Gallery in February, 2019

External Partners

- Bellamy Creek Correctional Facility, Ionia, Michigan

- Richard A. Handlon Correctional Facility, Ionia, Michigan

- Ingham County Youth Center, Lansing, Michigan

- Ionia Correctional Facility, Ionia, Michigan

- Michigan Reformatory, Ionia, Michigan

- Parnall Correctional Facility, Jackson, Michigan

MSU Collaborators

- Tessa Paneth-Pollak, Director, LookOut! Art Gallery, Residential College in the Arts and Humanities

- Kevin L. Brooks, Academic Specialist for Diversity and Civic Engagement, Residential College in the Arts and Humanities

- Center for Poetry, Residential College in the Arts and Humanities

- Center for Community Engaged Learning, Michigan State University

Form(s) of Engagement

- Community-Engaged Creative Activities

- Collaboratively created, produced, or performed writing, spoken word performances, and exhibitions

- Community-Engaged Teaching and Learning

Reading their poetry aloud to others encourages the incarcerated individuals' creativity and confidence in their imaginative expression.

Robert Frost said, "Poetry is when an emotion has found its thought and the thought has found words."

For those incarcerated, emotion and self-expression can be locked away as much as their physical selves. Guillermo Delgado and his students offer a way to find, articulate, and release those thoughts, through poetry, drawing, and other forms of creative expression.

Guillermo Delgado is an energetic and deeply dedicated artist-educator who believes engaging communities in "creative and empowering processes of art exploration" leads to better things. He applies that message to his work with students at the Residential College in the Arts and Humanities (RCAH), as well as the men in his prison classes.

It has been a winding journey for Delgado and his artistic and academic development.

"How did I end up at Michigan State University?" he pondered. "Good question, because I grew up in Chicago and thought I might become a priest. When the seminary ruled that out for me, I knew that there was something more in store for me out there."

As a self-taught printmaker and painter, Delgado developed his art career in various ways.

Two of Delgado's earliest exhibitions were in 1993 at Chicago's Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum ("Muertos de Gusto") and Museum of Science and Industry ("Latino Horizons"). His artwork has been featured in dozens of venues, including the Mexican Museum in San Francisco, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, The School of the Art Institute's Betty Rymer Gallery, Noyes Cultural Arts Center in Evanston, Illinois, Heard Museum in Phoenix, and Michigan State University. Delgado spends summers teaching at Ghost Ranch in New Mexico (the home and studio of Georgia O'Keeffe).

His love of poetry, especially haiku, has been incorporated into his work. Haiku is a Japanese poem that links two ideas together in seventeen syllables and three lines. It is a technique that uses very few words to bring a physical experience or sensation to a reader with only words. It is most often used to describe nature, seasons, or brief moments in time.

While working on his Master of Fine Arts in Interdisciplinary Arts at Goddard College, Delgado wrote a haiku-a-day for 100 days during a collaboration with a Chicago artist-run organization focused on a community bookbinding facility called the North Branch Projects.

Building Collaborative Partners

He came to MSU in 2008 as an artist-in-residence. In 2014 he established the prison poetry classes in multiple mid-Michigan prisons. It was a challenging way to establish partnerships. Each prison warden oversees daily operations, and Delgado worked with each of their offices to bring MSU programs and students to their facilities.

"There needs to be communication with everyone we encounter during prison visits," said Delgado. "I need to have all paperwork and prior authorizations in order. And we have to be ready to work with those prison students who have earned their seat in the class. If one thing is off, it can ruin all the plans for that day. I spend time making sure we have done everything possible to keep things running smoothly."

MSU students must pass background checks and adhere to rules when entering and exiting the prison.

"There is a protocol from the time we are allowed in the building," said Delgado. "Be respectful, dress appropriately, stay with the group. We have a serious responsibility, and I don't want to jeopardize the relationships we have built among the employees at the Michigan Department of Corrections. As a matter of fact, we work toward outcomes that reinforce the benefits of the classes and sessions. If we have the support of the correction officers, and if they can see positive outcomes as a result of our work, then we are able to sustain and build on what can be done."

At the Richard A. Handlon Correctional Facility, Vickie Ortiz and Jodi Heard have been supportive of Delgado's efforts to bring the poetry classes to the incarcerated. Their involvement contributes to the support and success of the program, and they work with Delgado and the MSU students to assure appropriate procedures are understood and followed.

What is a Zine?

Upon completion of his MFA, Delgado was hired in 2015 by RCAH as an academic specialist in community and socially engaged arts.

As his experiences with helping people unlock their creative expression accumulate, Delgado finds that nearly anyone can unlock that ability – especially if others are willing to offer examples and encouragement.

"A 'zine' is a creation, something tangible that lets you share your art with others. You can draw, paint, write what is important to you. I love helping others find the way to express what is deep inside them," said Delgado.

Poetry lessons are varied, and Delgado includes topics he thinks may appeal directly to incarcerated men. One example is the work of Etheridge Knight, an African-American poet who wrote Poems from Prison while serving an eight-year sentence for robbery.

During the assignments, the men are encouraged to explore different ways to create their poetry. Delgado has a sheet he distributes with the heading, "I Am Poem." It encourages the thought process with fill-the-blank lines such as, 'I wonder,' or, 'I feel,' or, 'I dream.'

He acknowledges that the work can bring about strong feelings. "Sometimes I sit in a coffee shop (near downtown Lansing), and think about what I've heard or seen." Delgado has learned to take that information and turn it back into his own artmaking. "It's my way of centering. I have to do that, because the RCAH students who are sharing these experiences also need to become aware of how to handle it. I recognize that there are multiple learning streams going on at the same time—mine, RCAH students, prison students, corrections officers and administrators, family members, and community members."

Prisoners earn their entry into Delgado's poetry class as a reward for good behavior and a commitment to education. Delgado introduces assignments that can be met with curiosity, resistance, indifference, or frustration. Haiku is one of the challenging assignments. Free form poetry can lead to deep introspection and, in some cases, funny stories.

Zines can be made into publications so that the work can be shared with others. You can assemble something using scissors, glue, and paper or you can use digital templates to share on the Internet.

Guillermo Delgado's exhibit featured artistic works by Delgado, MSU students, and incarcerated individuals, bringing to life their voices and experiences through the RCAH prison poetry courses.

The tangible product is a moment of pride for many incarcerated individuals. They have created something original and personal and lasting.

Poetry Slam with the 2019 Bluewater Poets

Poetry sessions conclude with a Poetry Slam, which is a competitive event where performers, named the Bluewater Poets, recite their poems in front of an audience. Delgado enlists five volunteers as judges, who bestow ratings of 1 through 10 (ten being the top honor) as each poet concludes. Competitors are judged on their poem content, as well as their delivery.

"According to William Wordsworth, the United Kingdom's Poet Laureate in the mid-1800's, "Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility." That sentiment can be applied to the poetry Delgado sees emerge from incarcerated individuals.

The topics—and the poems—can be raw:

"I'm doing this because I failed as a father, and I want to be a better role model for my two daughters," said one participant.

"I got here because I was loyal to the wrong people," said another, a former college football player who at one point had a promising future as an athlete.

Some of the most poignant poetry included sentiments about their mothers and grandmothers. Others talked about the violence they had witnessed, sometimes at a very young age.

Whether the incarcerated poet chooses to recite, sing, or rap, the performance can be powerful.

"You see the passion and the hurt and the pain and the anger. Sometimes it's a jumble, everything fighting to get out at once," said one MSU student.

Diarra Bryant received the top prize in the 2019 Bluewater Poets competition, just a few points shy of a perfect score. He was a repeat winner, earning the prize in 2018. He had shared his ambition during the final session prior to the poetry slam.

"I'm going for it," Bryant said to his classmates. "I've been working on it awhile, and it's gonna be good. I'm just warning you all."

Bryant entered prison as a teenager and is serving a life sentence at Michigan's Richard A. Handlon Correctional Facility in Ionia. He has been in prison for two decades and began to use his creative abilities by attending a weekly poetry workshop organized by Delgado.

"It's hard to write it down at first, because we are in an environment where you need to keep your reputation," said Bryant. "But now my thoughts just keep coming. I write them down as fast as they come."

The judging feels harsh, even within a prison. Men pour out their words containing private thoughts and soul-searching missteps, and the judges each write a score on a white board and show it to them at the conclusion of their performance. The judges' numbers are tallied and announced to the audience, the performer is excused, and the next person takes his place on stage to deliver his poetry.

Prizes are snacks and treats such as candy bars and chips, which are highly valued. That doesn't seem to be the primary reason that the incarcerated participate, however. As Delgado observes, "The poetry is where they can put some of that energy that can't go anywhere else. And, I think it gives them a chance to feel human and hopeful and in control. Whether they are talking about hard lessons, or good and bad memories, they are able to express themselves and release some of that energy. I am thankful that these programs are supported by RCAH, the students who go with me, and the incarcerated who work very hard to both get in the classes and complete the assignments. It is very rewarding work."

There have been additional outcomes from Delgado's work. Last spring, in conjunction with RCAH, Delgado hosted an exhibit "Rituals to Seed Clouds with Crystals," in which the art, poems, and photos from prison students were showcased.

As for the future? Delgado sees possibilities in so many endeavors. Along with poetry, he conducts yoga classes for the incarcerated, believing in the power of contemplative practices. He continues to collaborate with students, educators, and the community because he believes deeply in the transformative benefits of artistic expression through drawing, painting, and poetry—storytelling.

"I found what I love to do, and for that, I'm so thankful," said Delgado.

- Written by Carla Hills, University Outreach and Engagement

- Photographs courtesy of Guillermo Delgado