The Mainstay of Humanity: Grasslands Research

- Carolyn M. Malmstrom

- Associate Professor

- Department of Plant Biology

- College of Natural Science

Sheep survey grazing options on rangeland infested with invasive weeds. Exclosures in background keep sheep out of research plots in which different weed control methods are being tested in collaboration with a ranch owner.

According to Carolyn Malmstrom, "Grasses are the mainstay of humanity, feeding people both directly through grain production and indirectly through supporting milk and meat production. Two-thirds of our calories come from grasslands. These are the ecosystems most impacted by people." Lands with good soil and water availability are converted to grass crops, as in the central U.S. prairies. Other places with poorer soils are used for grazing, as in the Sahara or the western United States.

Dr. Malmstrom's lab studies the ecosystem dynamics of disturbances such as the introduction of exotic species, which can become invasive. Semi-arid grasslands in California, where she is just now finishing up a major USDA-funded research project, are a case in point. Malmstrom noted that there have been "two major changes in the region's vegetation over time. First the native perennial grasses were replaced by annual forage grasses that were introduced with the Spanish settlement. These species do not have the same conservation value as the original native perennials, but they produce good forage and for a long time they were the mainstay of ranching. But now these introduced species are being replaced by a new wave of noxious weeds with little to no forage value."

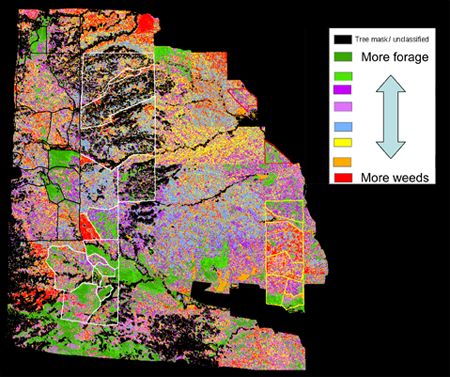

Weed patch distribution across California rangeland watershed under study, derived from time series of aerial photography.

Why are the weeds taking over? "The weeds don't have the same seasonal timing," explained Malmstrom. "The forage grasses are cool-season species that avoid the summer drought. They germinate in November and grow through the rainy winter. Their growth really takes off in March; then they flower in April and have usually set seed and died by May. The weeds are able to hang on longer and stay green into June. We wanted to know how they do that, when there's so little rain between May and October in this system."

To find answers to this and other questions, Malmstrom and her team worked closely with local ranchers and conservation agencies. "The ranchers are interested in reducing the weeds and restoring the forage grasses, along with some native perennials," she said. "They made suggestions about what they thought was

happening and we brought in scientific tools to experiment further. We worked together to conceptualize and test hypotheses."

Graduate assistant Abbie Schrotenboer (L) and Carolyn Malmstrom (R) check grass samples at the MSU greenhouse.

The partners started to see solutions when they looked at the timing of grazing. "It's intuitive to graze at the peak of the forage grasses' growth in spring, when they're the most lush and green. But it turns out this creates more weeds," said Malmstrom. "If you graze in the spring, it depletes the good forage at the time it's using the most water—thus leaving more moisture for the weeds that come later." And, in fact, the ranchers started to have more success when they switched to grazing in the fall.

Malmstrom values the ranchers' contribution to her project. "All of them are thoughtful and strive to be good stewards," she said. "All of them have other jobs that help support their ranching operations. Through these jobs, they absorb the cost of preserving the open-space view and wildlife habitat that we all enjoy." However, she cautioned, "It's important to be culturally sensitive. Academics don't always understand the partner's point of view. For example, you need to pay attention to functional details on a ranch—leave the gate the way you found it! Remember whether it was open or closed when you went through."

The project has also strengthened Malmstrom's conviction that "basic and applied science are not opposites." The goal of her work is to "illustrate processes that are basic and also important to realworld applications," she said.

- Written by Linda Chapel Jackson, University Outreach and Engagement